As the old joke goes, if all the economists in the world were laid end to end, they would not reach a conclusion. Likewise, if you were to ask a lawyer, an economist, and a political scientist to define what a local government is, you would most likely get three very different definitions.

Since development takes place in the cities, towns, and rural communities where people live and work, the ability of local governance institutions to promote inclusive and equitable development at the local level matters a lot. For instance, whether (or the extent to which) a local government has political, administrative, and fiscal autonomy and authority determines the ability of local officials to make their own decisions in a way that responds to the needs and priorities of their own constituents.

As such, understanding the nature of subnational governance institutions and multilevel governance systems is likely to have real-world implications for the ability of countries to pursue inclusive governance and sustainable development through more inclusive and effective decentralization and localization.

LPSA’s LoGICA framework

LPSA’s Local Governance Institutions Comparative Assessment (LoGICA) framework aims to inform and elevate the global debate on decentralization and localization by comparing multilevel governance systems and subnational governance institutions around the world.

In doing so, the LoGICA framework makes a clear distinction between subnational governance institutions—a general term capturing a range of different types of subnational public sector institutions—versus subnational government institutions, which are subnational institutions that adhere to a number of specific institutional characteristics.

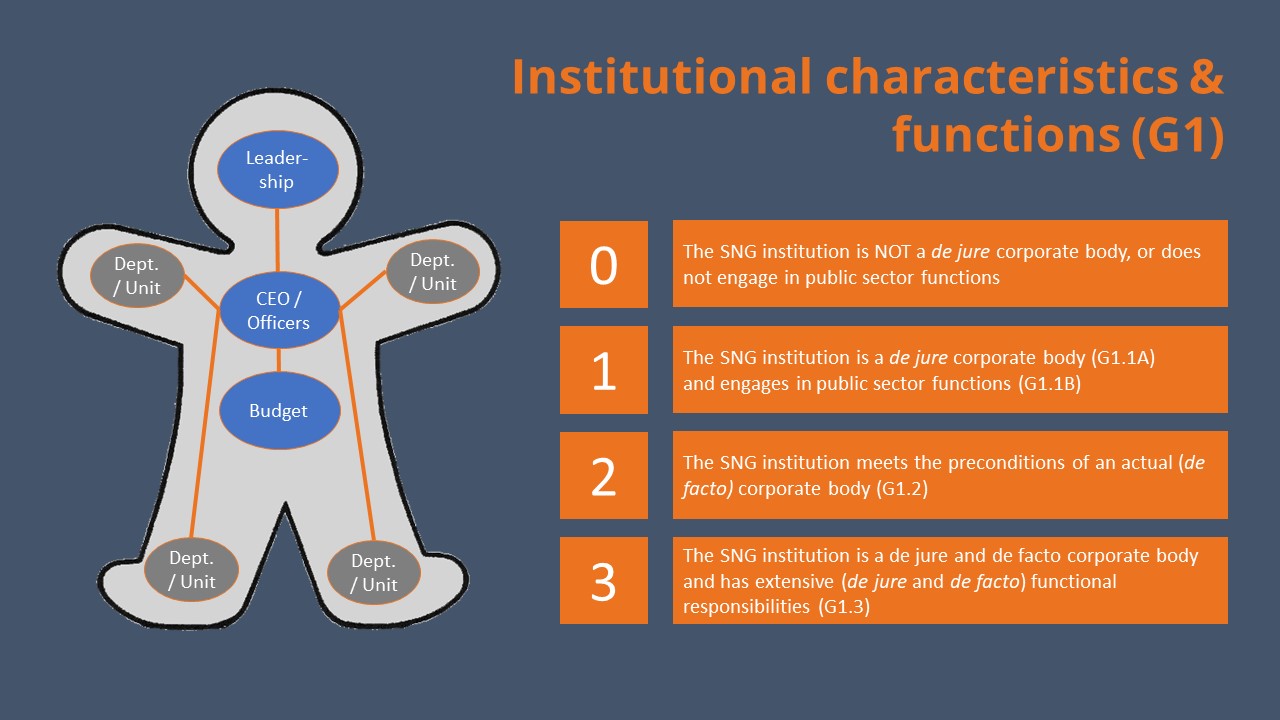

Specifically, the LoGICA framework defines subnational governments as corporate bodies (or institutional units) that perform one or more public sector functions within a subnational jurisdiction and that have adequate political, administrative, and fiscal autonomy and authority to respond to the needs and priorities of their constituents.

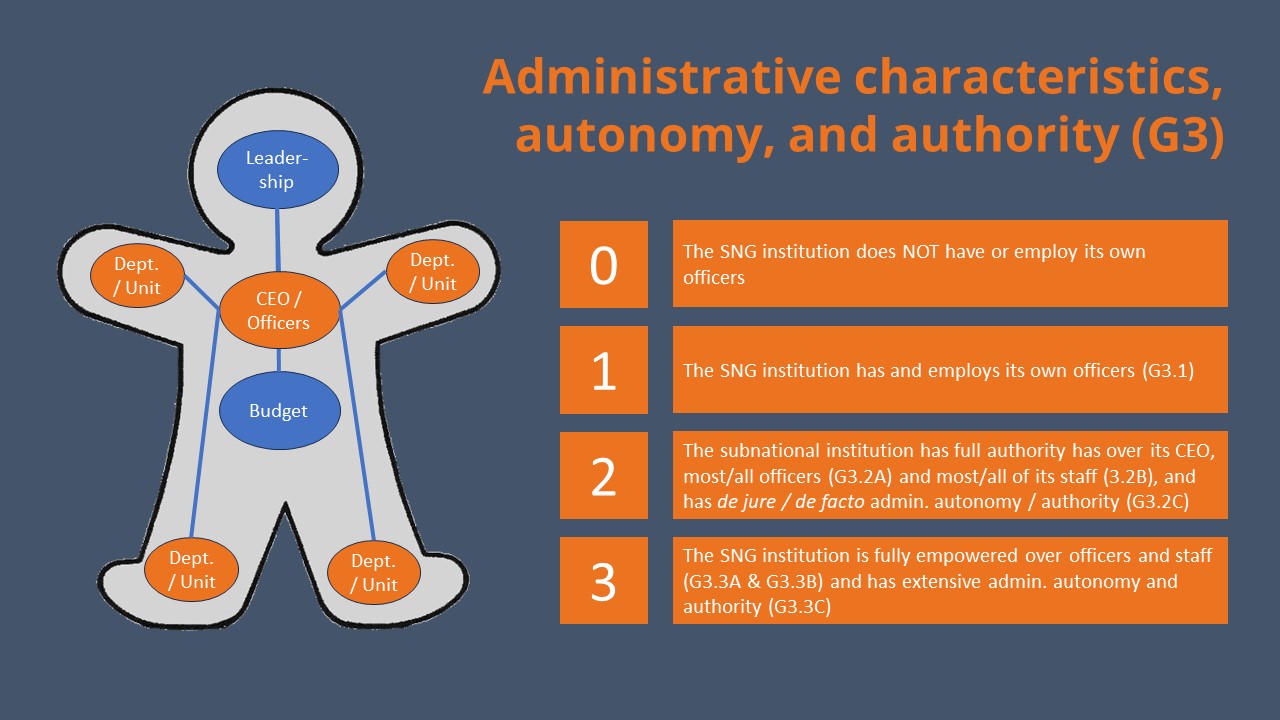

Based on the definitions used by the International Monetary Fund, OECD, World Bank and others (as part of the IMF’s Government Finance Statistics and the System of National Accounts), LoGICA’s definition implies that regional and local governments—as corporate bodies or institutional units—have a degree of institutional autonomy and authority, including the ability to own assets, raise funds, and engage in financial transactions in their own name. Subnational governments should also be able to appoint their own officers, independently of external administrative control.

While regional and local governments in OECD countries—especially in North America, the European Union, and Australasia—are (almost) all corporate bodies with considerable autonomy and authority, both by law and in practice, the extent to which this is the case in other global regions is unclear. As a result, LPSA partnered with subnational governance experts in over a dozen countries in Africa and Asia in 2022 and 2023 to prepare an initial set of LoGICA Intergovernmental Profiles.

Based on our emerging findings, the LoGICA framework was further refined in December 2023 to ensure that the framework provides an accurate and consistent comparative assessment across different country approaches to decentralization and localization.

Four types of subnational governance institutions

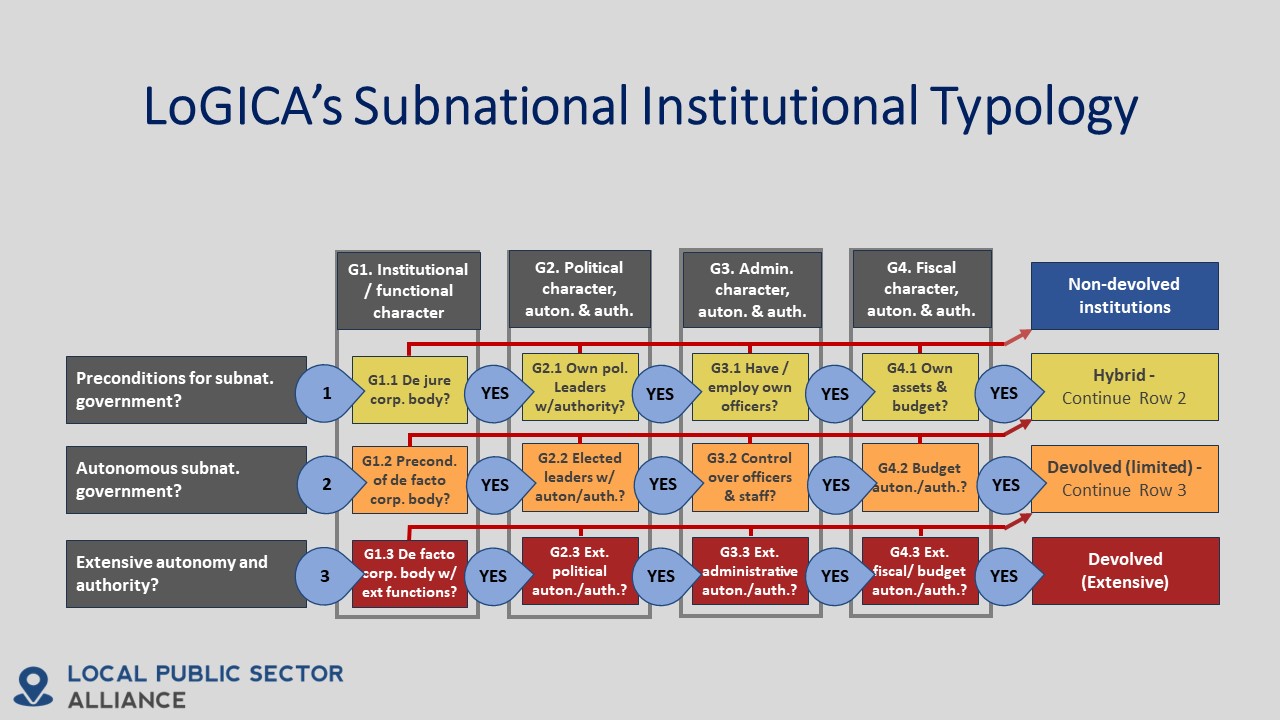

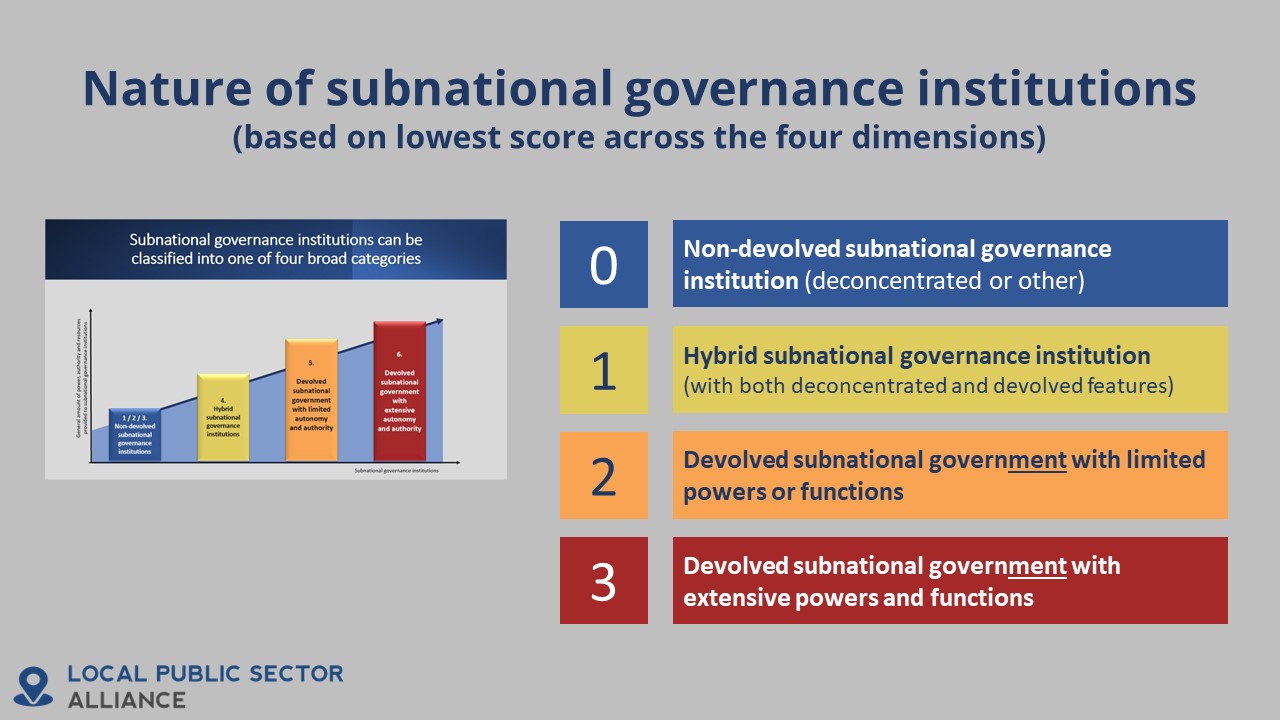

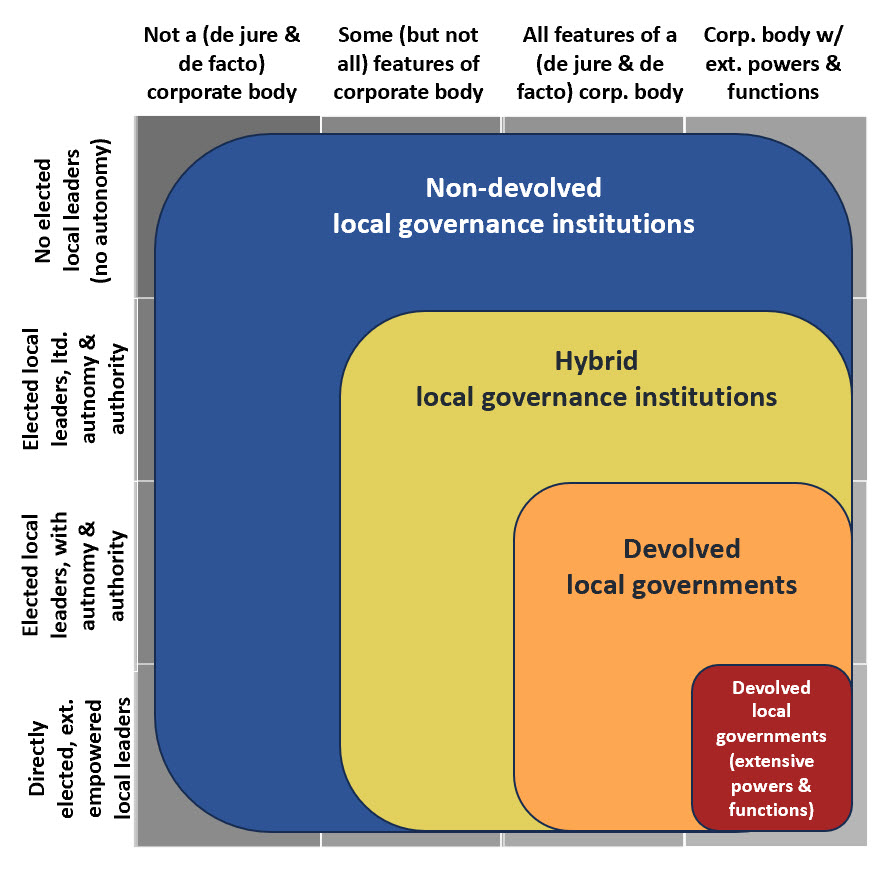

In order to identify the nature of subnational governance institutions in different countries, the LoGICA framework considers four main categories of subnational governance institutions: non-devolved subnational governance institutions; hybrid subnational governance institutions (combining features of devolution and deconcentration); devolved subnational governments with limited powers and functions; and devolved subnational governments with extensive powers and functions.

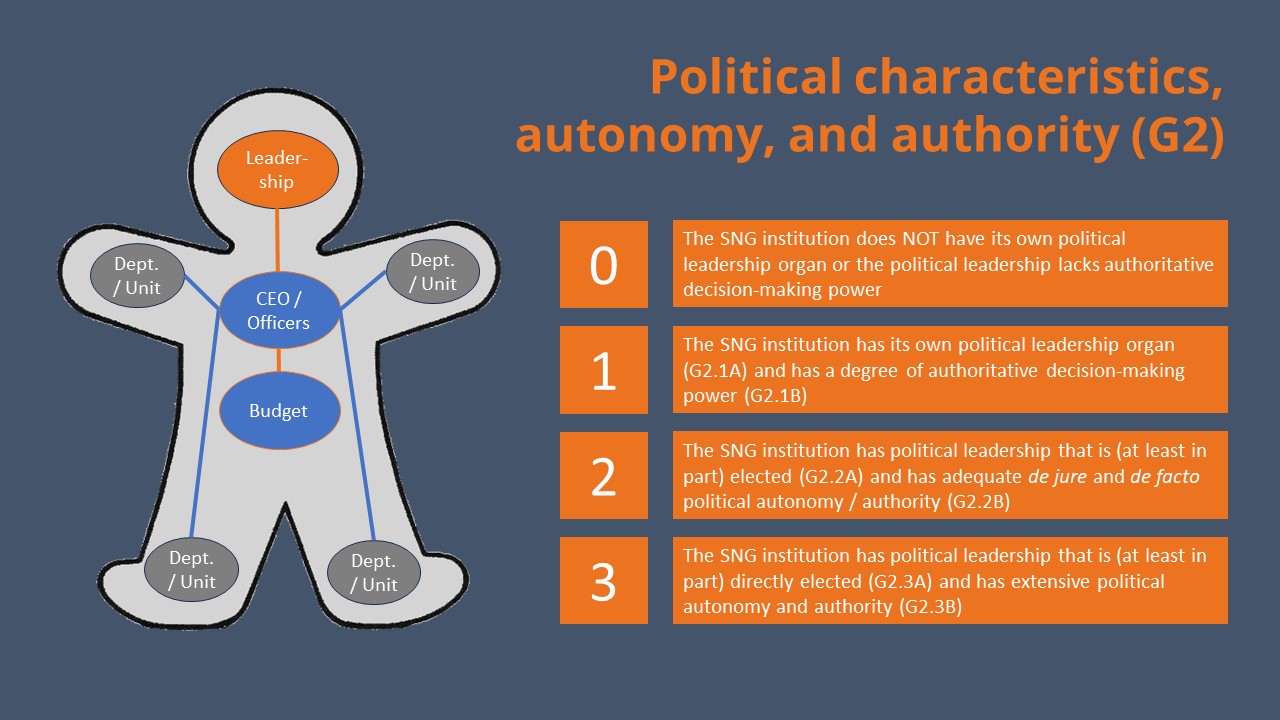

Many political scientists equate the presence of elected regional and local representative bodies to the existence of regional and local governments. However, in some countries, legislation establishes local governments as de jure (legal) corporate bodies, while subsequently failing to give them the legal powers needed (e.g., control over their own officers; authoritative power over their own budget) to actually function as corporate bodies or institutional units. As part of the LoGICA framework, classifying the nature of subnational governance institutions should be based on the de facto situation, rather than based on the de jure situation.

Our initial assessment of local governance institutions in Africa and Asia identified many cases where subnational leaders were elected, but where these elected leaders in practice (de facto) were not empowered to lead a corporate body or institutional unit. Without being institutionally empowered as a single body, these subnational institutions lack the autonomy and authority to effectively implement their constituents’ priorities.

The refinement of the LoGICA framework (December 2023) therefore considers in great detail not only the political or elected nature of subnational bodies, but also considers the detailed institutional (including administrative and budgetary/fiscal) aspects of subnational governance to determine the nature of local governance institutions.

Identifying the nature of subnational governance institutions

Identifying the nature of subnational governance institutions requires consideration of four aspect of the subnational organization:

- Institutional characteristics & functions

- Political characteristics, autonomy, and authority

- Administrative characteristics, autonomy, and authority

- Fiscal/budgetary characteristics, autonomy, and authority

Institutional characteristics & functions. The institutional characteristics and functions of subnational governance institutions vary widely across different countries. In some countries, subnational governance institutions do not have any features of a corporate body or institutional unit (e.g., is part of a higher-level government organization). In other countries, by law and in practice, subnational governance institutions have all the features of a corporate body or institutional unit, and are (de facto) responsible for multiple public sector functions.

Political characteristics, autonomy, and authority. Similarly, the political characteristics, autonomy, and authority of subnational governance institutions vary widely across different countries. In some countries, subnational governance institutions do not have their own political leadership, or its political leadership does not have any political autonomy or authority. In other countries, by law and in practice, subnational governance institutions have directly elected political leadership with extensive political autonomy and authority.

Administrative characteristics, autonomy, and authority. Third, the administrative characteristics, autonomy, and authority of subnational governance institutions vary widely across different countries. In some countries, subnational governance institutions do not have any administrative autonomy or authority (e.g., is an administrative part of a higher-level government organization). Yet, in other countries, by law and in practice, the subnational governance institutions have extensive administrative autonomy and authority to appoint and fully control all of their own officers; to determine their own organizational structure; and to appoint and control all of their own staff.

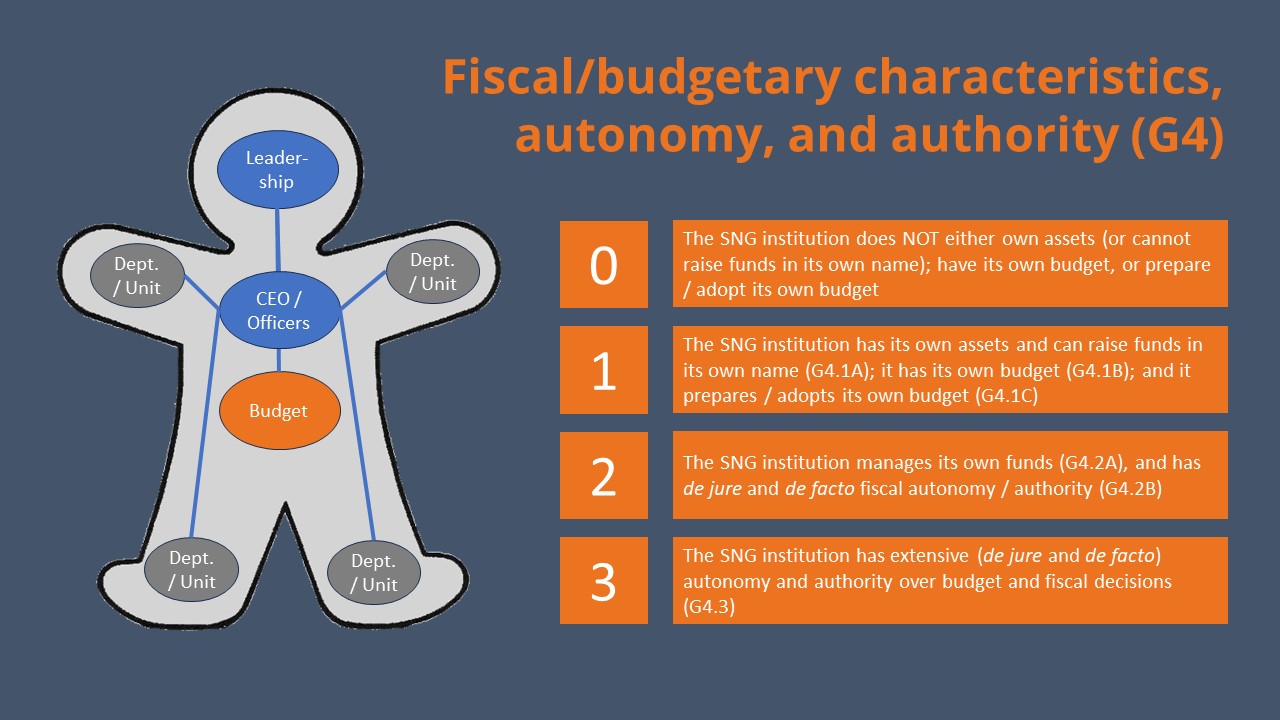

Fiscal/budgetary characteristics, autonomy, and authority. Finally, the budgetary or fiscal characteristics, autonomy, and authority of subnational governance institutions can vary widely across different countries. In some countries, subnational governance institutions do not have their own budget, or the subnational political leadership does not prepare and approve its own budget. In other countries, by law and in practice, subnational institutions have extensive fiscal/budget autonomy and authority to prepare, approve and manage their own budgets and funds without approval or interference from higher-level officials.

Classification and caveats

The classification of subnational governance institutions depends on these four dimensions (institutional, political, administrative and fiscal). In fact, given that subnational governments need autonomy and authority in all four of these dimensions in order to effectively selected and implement their constituents’ priorities, the nature of subnational governance institutions should be based on lowest score across these four dimensions.

Finally, it is important to remember that determining the structure and nature of subnational governance institutions is only a small first step in better understanding multilevel governance systems.

Decentralization or multi-level governance systems are highly complex systems. Thus, in addition to understanding the structure and nature of subnational governance institutions (as defined by LoGICA’s Intergovernmental Profile), it is important to understand the details of the different (political, administrative, sectoral, fiscal) dimensions of the multilevel governance system within which subnational governance institutions operate. These details are explored as part of the Country Profile that is part of the LoGICA Framework. After all, the inclusiveness and effectiveness of the multilevel governance system as a whole is determined not just by the structure and nature of subnational governance institutions, but also by the details of the multilevel governance system within which they operate.