An effective multilevel public sector requires public stakeholders at different levels of government to work effectively—and work together effectively—in order to ensure that public spending is transformed into resilient, inclusive, sustainable, efficient and equitable public sector programs and results. A big picture look at decentralization requires consideration of the main dimensions of decentralization, including political, administrative and fiscal dimensions. When the focus is on a specific sector, it may further be appropriate to consider sector-specific issues as separate from other aspects of public

administration.

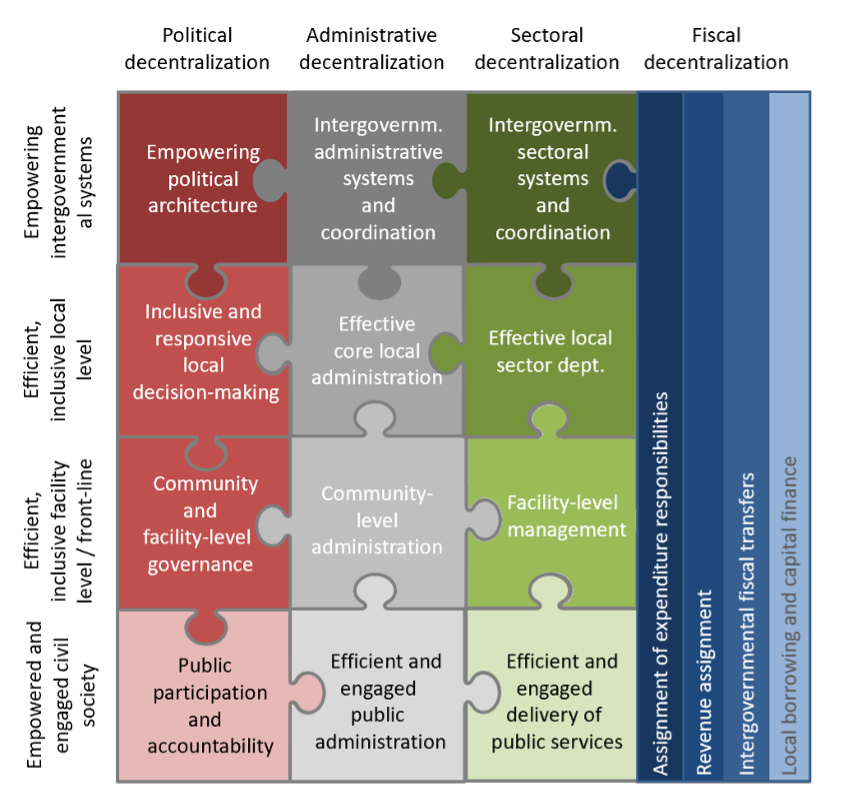

Establishing effective multilevel governance systems requires action and coordination across different levels of government. It also requires an empowering intergovernmental architecture and systems at the central government level; efficient, inclusive and responsive local governments and/or other institutions at the local level; an efficient and well-managed system of frontline service delivery facilities or providers; and an engaged civil society, citizenry, and local private sector.

Establishing effective multilevel governance systems requires action and coordination across different levels of government. It also requires an empowering intergovernmental architecture and systems at the central government level; efficient, inclusive and responsive local governments and/or other institutions at the local level; an efficient and well-managed system of frontline service delivery facilities or providers; and an engaged civil society, citizenry, and local private sector.

The resulting assessment framework for decentralization, intergovernmental relations, and the local public sector (Figure 1.1) is formed by a 4 X 4 matrix representing the dimensions and levels of an effective multilevel public sector. Figure 1.1 locates fiscal decentralization within this framework. The following sections of this primer will unpack four pillars of fiscal decentralization (the last column in the figure) and discuss how they relate to the constituent elements of a multilevel public sector.

1.1 The four pillars of fiscal decentralization

The theoretical argument for fiscal decentralization is formulated as: “each public service should be provided by the jurisdiction having control over the minimum geographic area that would internalize benefits and costs of such provision.” In a fiscally decentralized system, the policies of subnational branches of governments are permitted to differ in order to reflect the preferences of their residents. As such, designing a fiscally decentralized intergovernmental system requires focusing on four areas, which are referred to as “pillars”:

- Expenditure assignment: the assignment of expenditure powers, functions, and service delivery responsibilities at the various levels of government.

- Revenue assignment: the assignment of revenue powers and division of responsibilities across revenue administrations.

- Intergovernmental fiscal transfers.

- Local government borrowing, debt and capital finance rules, responsibility, and accountability.

Although these four pillars are a useful construct that help to discuss and explore the various dimensions of fiscal decentralization, they are closely related to each other in line with the concept that “finance should follow function.” This means that through the first pillar, understanding the assignment of powers, functions, and expenditure responsibilities within the public sector – the “expenditure assignment” – indicates the level of expenditure requirements or the “expenditure needs” of different administrative levels and different local or regional government units. However, public sector resources are scarce and need to be prioritized. As a result, actual expenditures at all government levels often fall short of the “needs” or desired level of expenditures. To a large extent, the level and composition of local expenditures is driven by the availability of resources to be examined through the remaining three pillars: local own source revenues (OSR); intergovernmental fiscal transfers (IGFT); and borrowing or other debt financing mechanisms (FIN).[1] As such, the relationship between the four pillars in a balanced budget environment may be captured by the following notation EXP = OSR + IGFT + FIN. The composition of funding sources is different in different countries and in different sectors. In general, decentralization of public policy making power involves transfer of legal and political authority for planning projects, making decisions, and management of public functions from the central government and its agencies to subnational governments. The transfer of authority and responsibility over public functions from the central government to subordinate or quasi-independent government organizations covers a broad range of topics. There is also no prescribed set of rules governing the decentralization process that apply to all countries. Decentralization takes different forms in different countries, depending on the objectives driving the change in the structure of government. While distinguishing among different types of decentralization is useful for pointing out its many forms, it is important to highlight the interlinkages between the pillars of an intergovernmental fiscal system.

There is no easy answer to the question of how to design a decentralized system to promote transparency, accountability, and efficiency in public service delivery. This primer presents conceptual discussions on the design of an effective intergovernmental system, synthesizing academic and policy literatures as well as lessons learned from country applications. However, before the discussions on the pillars of fiscal decentralization, it is helpful to provide an overview of the complex service delivery and fund flow arrangements at the local level as they influence the design of intergovernmental system in every country.

1.2 An overview of intergovernmental finance and funding flows

The distinct challenge of intergovernmental finance is the large number of stakeholders and “nodes” in the system, which can make it much more complex to understand and track. A more detailed perspective on the interrelationship of the four pillars is provided in Figure 1.2, which presents a generic picture of the key institutional stakeholders in a multilevel public sector and highlights the typical funding flows among them.[2]

First, the assignment of powers, functions, and expenditure responsibilities is an important factor in determining the relative size and composition of the expenditures of the national government, local governments, national parastatals, authorities, or agencies like a National Road Fund, and other local-level entities or authorities (such as local water utilities—indicated in the figure by Line # 1. Naturally, the ability of different stakeholders to fund their respective expenditure responsibilities is determined in the first instance by the assignment of revenue powers and the ability of government units at different government levels to effectively collect revenues from the sources assigned to them (Line # 2). In practice, however, and for good reasons, as further discussed below, the revenue-raising power assigned to local and/or regional governments often falls (far) short of the expenditure needs of subnational jurisdictions. As a result, intergovernmental fiscal transfers are provided to help fill the gap between local expenditure needs and local own source revenues (Line # 3). Additionally, subnational borrowing and capital finance can play a useful role, particularly in funding subnational infrastructure. In practice, however, borrowing and capital finance typically play a relatively small role in intergovernmental finance in most countries (Line # 4).

Traditionally, discussions of fiscal decentralization have tended to focus largely on devolved local government expenditures and revenues (Lines # 1A and 2A), along with intergovernmental fiscal transfers (Line # 3). Other mechanisms of decentralization and localization are increasingly understood to be important as frontline public services tend to be delivered through a combination of devolution, deconcentration, delegation and centralized provision – often concurrently in a complex and often messy mix of financing modalities. As such, Figure 1.2 explicitly takes these alternative mechanisms of decentralization and localization on board.

The first of these three alternative channels of decentralization and localization includes the direct and deconcentrated public expenditures by the central government in support of frontline services (Line # 1B). This category of localized expenditures includes a range of central government-led mechanisms to localize public interventions, such as vertical sector programs; deconcentrated service delivery; community-driven development programs; and direct cash transfer programs. These mechanisms all tend to involve direct delivery and funding of public services through on-budget central government expenditures, although these expenditures may have different implications for effective public sector management and effective public financial management (PFM) when compared to “regular” (headquarters-level) central government spending.[3]

A second mechanism for non-devolved decentralization and localization comprises spending on frontline services by parastatal entities, national authorities, national investment funds and similar entities (Line # 1C). The distinguishing feature of this category is that these entities tend to be off-budget at the central government level and outside the direct hierarchical control of the central government. Examples of such national entities, authorities, and funds include traditional parastatal entities such as a National Medical Supply Agency, a National Transit Corporation or National Water Authority, national hospitals, and national universities. There are others such as a National Roads Fund Authority, National Health Insurance Fund, Municipal Investment Fund, and other similar funds. These entities typically derive some or all of their funding from the central government ministries under whose authority they operate, in addition to any direct or indirect user fees and charges that the entity may be authorized to collect.[4][5] Depending on the exact combination or permutation of decentralization and localization modalities used, in different sectors these national entities can account for a large and often overlooked portion of sectoral funding.

A final non-devolved channel of spending on local public services is formed by semi-autonomous local service delivery providers whose finances are not included in the local government budget (Line # 1D). This grouping includes local providers that typically form the “last mile” of service provision, and include municipal utility companies, urban development authorities, and so on. Note that Figure 1.2 only highlights local service providers and facilities that have a degree of institutional and budgetary autonomy; to the extent that frontline facilities are operated “on budget” by the local government, the revenues and expenditures of these facilities are simply understood to be part of the local government budget.

In different countries and in different sectors, local service delivery providers may have a degree of institutional and financial autonomy. While local providers are sometimes corporate entities created, owned, or operated by local governments—for instance, under a board appointed by mayor or municipal council—in many other cases, such institutions are created or accountable to higher-level government authorities. As such, these local service delivery entities fund or deliver public services in coordination with – or sometimes, in a parallel and duplicative manner to – local governments. Given the off-budget nature of these entities, any funding received by these entities—whether from local government budget, national entities, or from tariffs, fees, or other payments—has traditionally been overlooked by the literature on fiscal decentralization.

The subsequent four sections of this note (Sections 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively) provide a brief technical introduction to each of the four pillars of fiscal decentralization. Each of the sections will summarize the relevance of each pillar of fiscal decentralization, provide an overview of devolved intergovernmental finances in relationship to each pillar, and present an overview of non-devolved intergovernmental finances in the context of each pillar.

1.3 Real-world obstacles, the political economy of fiscal decentralization and entry points for development partners

Decentralization reforms and other public sector processes are not just technical processes to be decided by technocrats; rather, they reflect a political or institutional contestation of power between different groups and individuals across and within different government levels.[6] As such, the design of fiscal decentralization, or a country’s intergovernmental fiscal architecture, should not only be considered through a technical lens, but should also be understood in the context of the political economy forces that help define it.

Beyond providing a technical overview of each of the four pillars of fiscal decentralization—in the context of complex intergovernmental fiscal systems that often rely on different approaches to decentralization at the same time—this note tries to identify some of the real-world obstacles encountered by policy makers and advocates for inclusive and effective decentralizatin and localization in supporting (fiscal) decentralization reforms and multilevel public sector strengthening. With this in mind, as part of the discussion of each of the four pillars of fiscal decentralization, each of the subsequent sections highlights common obstacles encountered in policy practice and a brief political economy perspective on each pillar.

In addition, Section 6 specifically raise implications for engagement by policy makers and development partners in fiscal decentralization and multilevel government finance, in terms of helping to identify possible areas of technical intervention in strengthening the intergovernmental fiscal systems.

[1] This nomenclature is especially relevant for devolved local government entities. The concept of the four pillars is the equally relevant for other (non-devolved) local-level entities, such as deconcentrated local administration units or local service delivery providers, authorities or facilities. For non-devolved countries, the context and terminology for the four pillars would have to be adjusted slightly to apply to the specific institutional setting.

[2] This diagram shows a public sector with a national (central) government and one subnational (local) government level. By extension, one or more additional levels of subnational (regional and/or local) government may exist in a country.

[3] The diagram does not show deconcentrated administration units as a separate box, as deconcentrated spending units are ultimately an integral part of the central government budget. In specific instances, it might be useful to visualize expenditures by deconcentrated spending units as a separate box in the diagram. The flow of funds between the central government and deconcentrated spending units would be considered subnational budget allocations, rather than intergovernmental fiscal transfers.

[4] In developing and transition countries, such national entities, authorities and funds often derive part of their funding from the World Bank, other international financial institutions, and development partners.

[5] Since these national parastatals or authorities are part of the central government, funds flowing from the central government budgets are technically not considered intergovernmental fiscal transfers.

[6] For an introductory discussion on the political economy of decentralization, see “Section 3: Understanding the political economy of decentralization and intergovernmental relations” in Decentralization, Multilevel Governance and Intergovernmental Relations: A Primer (LPSA/World Bank 2022).