Three years after the introduction of a new federal constitution, 2019 is going to be a critical year for fiscal federalism in Nepal.

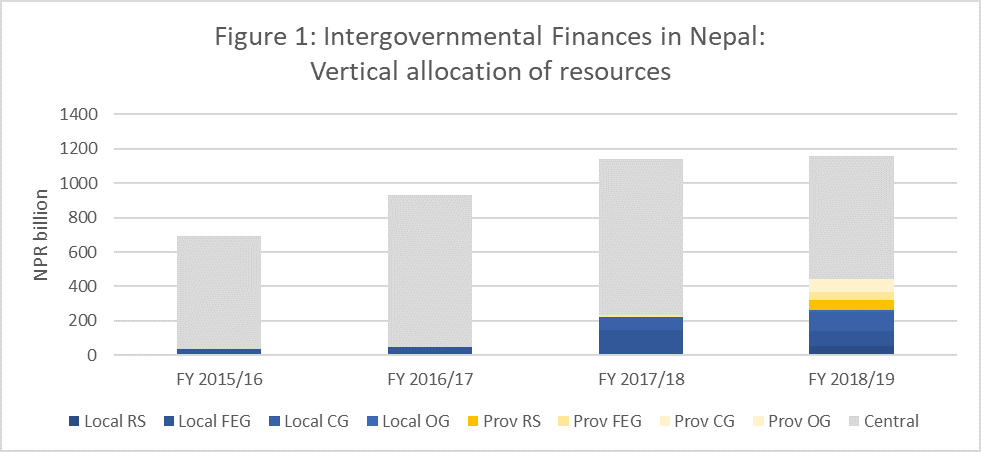

One of the great successes of Nepal’s path to federalism has been the quantity of financial resources that has been shifted from the central (now federal) government level to the local government level, making Nepal the most decentralized country in South Asia. Whereas a few years back, local bodies only received a few percent of national financial resources, during FY 2018/19, local governments are expected to receive around 24 percent of public sector funds, while provincial government are set to receive another 16 percent of public sector finances (Figure 1).

However, shifting resources to the provincial and local governments level is a necessary—but not sufficient—condition for successful decentralization. When decentralization is defined as “the empowerment of the people through the empowerment of their local governments” (Bahl and Bird, 2018), then successful decentralization requires that—first—a sound intergovernmental fiscal transfer system is in place, and—second—that mechanisms are in place to ensure that local governments use these resources effectively for the benefits of their constituents. As such, the success of decentralization should not just be measured by the quantum of resources shifted to the local level, but rather, by the improvements in the efficiency and equity with which these funds are transformed into local public services.

Much remains to be done on this front, as the current intergovernmental fiscal systems does little to make sure that local governments effectively serve their constituents in the various areas over which the constitution gives them powers and functional responsibilities.

Whereas the first three years of Nepal’s transition have focused on establishing elected provincial and local governments and providing them with rudimentary staff and adequate financial resources, the coming year will be a critical year to ensure that the intergovernmental fiscal systems are in place to ensure that the implementation of the federal constitution leads not only to the empowerment and enrichment of local governments, but—in fact—to the empowerment of the people.

So what needs to get done in 2019 as the government gears up for the 2019/2020 financial year?

1. Clarifying the structure of the grant system (to make sure that finances follow functions)

The federal constitution defines four types of federal transfers or grants to provincial and local governments: (i) federal equalization grants, (ii) conditional grants, (iii) complementary (matching) grants, and (iv) special grants. The Intergovernmental Financial Arrangements Act (IFAA, 2017) further introduced the formula-based sharing of revenues from domestic VAT and excises—of which provincial and local governments each receive 15%. This revenue sharing—although in some ways duplicative with the federal equalization grant—was first implemented during the 2018/19 financial year.

While the Constitution and the IFAA set the ground rules for fiscal decentralization in Nepal, the Act does little to clarify what grant mechanism is intended to provide funding for what functions: for instance, is the Fiscal Equalization Grant exclusively intended to fund local infrastructure priorities, or should these resources also be used to fund key sectoral services (such as local education and health)?

It is impossible to make sure that provincial and local governments receive adequate funding for their constitutional mandates without being more explicit about the constitutional functions that each grant mechanisms is intended to fund. Furthermore, without such clarity, it is impossible for people to hold their local government officials accountable for their performance, as local officials would likely blame any service delivery shortfalls—whether justified or not—on inadequate intergovernmental funding.

In fact, in practice, many of the current grant flows reflect transition arrangements rather than a clear policy vision: for instance, wages for teachers and health workers are currently funded as conditional grants, whereas the constitution prescribes that conditional grants should be provided for funding infrastructure projects. Thus before modifying the vertical and horizontal allocation of grant resources to ensure that resources are distributed in an efficient, equitable and sustainable manner, it will be necessary to define which grant types should fund which local government functions in line with the constitutional mandates of local governments.

2. Activate local government powers and responsibilities through clear local planning and budget guidelines

During the first two years of the new federal system (2017-18 and 2018-19), the emerging local governments were instructed to act in many ways as the local bodies before them, planning in a bottom-up manner for community infrastructure priorities in a rather fragmented manner. While inclusive and participatory planning is an important element of the new federal system, the previous bottom-up approach to local planning and budgeting overlooks that local governments are now responsible not only for local infrastructure priorities, but also for many key public services that are national development priorities, such as public education, local health services, agricultural extension services, and many other local public services that were previously outside the scope of Local Bodies.

Planning and budgeting for these sectoral services requires technical knowledge that generally neither the newly elected local government leaders nor newly appointed local administrators currently possess. In the absence of clear guidance or support, many local governments have directed the vast majority of budgetary resources towards small-scale infrastructure projects that are popular with their constituents, while all but ignoring their new functional mandates. If this pattern is allowed to continue into 2019/20, there is a significant risk of the federal constitution failing to deliver on its promise of greater empowerment and better services to the people.

As such, it is up to the planning and budget guidelines to be issued by the Ministry of Finance (together with MOFAGA and the NNRFC) to provincial and local governments ahead of the 2019/20 financial year to clarify how they should adequately plan for their various constitutional mandates—including for sectoral functions of critical national importance, such as basic education or local health services, where detailed technical (sectoral) guidance is needed to prepare plans and budgets.

3. Reviewing the horizontal allocation formulas used for grant funding

During the first two financial years of the implementation of the federal constitution (2017-18 and 2018-19), allocation formulas were devised by the Ministry of Finance and the nascent NNRFC upon which resources were distributed among the country’s 7 provinces and 753 local governments. Given that the emerging local government were yet to meaningfully take up many of their constitutional mandates (such as public education or local health services), the exact details of the different horizontal allocation formulas were not highly critical. Instead, for the first two years of the new intergovernmental fiscal system, the most significant improvement in the horizontal distribution of financial resources was that the federal government was applying an objective allocation formula at all, as opposed to making allocation decisions in a discretionary (non-formula-based) manner.

However, now that local (and provincial) governments are increasingly expected to take on their constitutional mandates, including in key sectoral areas, it will be increasingly important that the horizontal allocation of financial resources corresponds to the different expenditure needs of local (and provincial) governments.

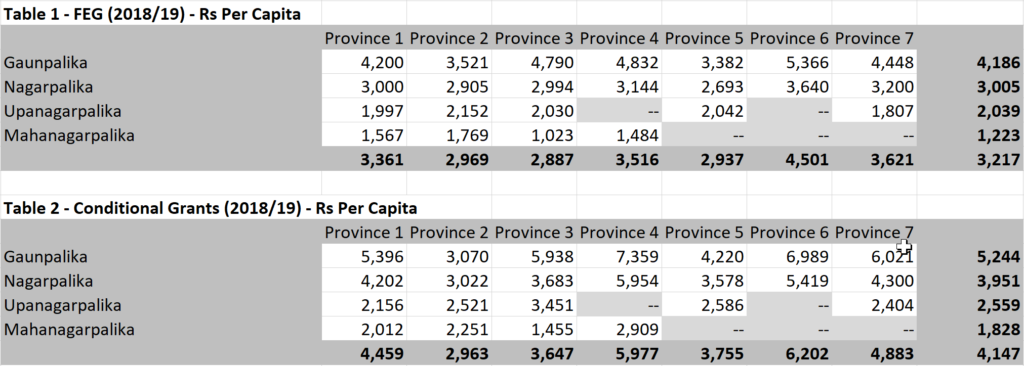

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the horizontal allocation of equalization grants and conditional grant resources in Nepal tend to vary considerable across different types of local government, and tend to favor less populous local governments, which are predominantly located in more mountainous regions. In particular, larger (more populous) urban local governments receive considerably smaller resources per person. This allocation pattern seems to be informed by a policy that emphasizes equalization over economic growth, and by a belief that there are significant scale economies in local administration and local service delivery—well beyond what is traditionally accepted to be the case by public finance economists.

Although the horizontal allocation formulas used for the first two years of the transition served their purpose adequately, the allocation formulas will need to be fine-tuned in 2019 and beyond. First, there is a need to review and revisit the horizontal allocation formulas for the equalization grant and revenue sharing in order to achieve a more efficient and equitable allocation of resources that is more in line with the true expenditure needs associated with the constitutional mandates of local governments. Second, there is a need to adhere more closely to universally-accepted principles of sound transfer design as many of the allocation factors currently included in the FEG formula are based on complex indices—for which the data or methodology may be inadequate and for which the link to local public service delivery is unclear—rather than being based on simple and transparent measures of local expenditure needs for which reliable data are readily available.

4. Improve the transparency of the intergovernmental fiscal system

In order to ensure that the intergovernmental distribution of public finances is accepted by stakeholders at all level as objective and fair, it is important to ensure that each step of the grant allocation process is fully transparent and contestable.

In fact, greater transparency is required during each step of the intergovernmental finance process, including (i) the detailed formulation and computation of the proposed formula-based grant allocations (including the underlying data) prior to the adoption of the intergovernmental allocations; (ii) the detailed grant allocations included as part of the approved national budget (including detailed allocations for each specific conditional grant schemes); (iii) detailed and timely information about the disbursement of grants during the budget year; and (iv) reconciliation and analysis at the end of the budget year to show that all grants were disbursed in line with the formula-based ceilings contained in the budget, and that resources were spent in line with their intended purpose. As a result of the greater transparency and contestability of the grant system, provincial and local governments—individually and collectively, on behalf of their constituents—will be better positioned to advocate for more equitable vertical and horizontal distribution of revenues, in line with their relative expenditure needs.

Achieving greater transparency, legitimacy and contestability will require national officials to make much (if not all) of the existing data regarding intergovernmental fiscal transfers publicly available on a regular basis. In addition, it will require greater effort to ensure that all provincial and local governments report their expenditures to the federal Ministry of Finance through the Sub-National Treasury Regulatory Application (SuTRA).

5. Establish constitutional leadership over the intergovernmental finance system

Nepal’s constitution specifically pursued a federal form of

government—with horizontal and vertical checks and balances on power—in order

to end “all forms of discriminations and oppression created by the feudal,

autocratic, centralized and unitary system”. In line with this objective, the

constitution established a National Commission—the National Natural Resources

and Fiscal Commission (NNRFC)—to ensure that intergovernmental finances would

be managed to benefit all Nepalis—rather than risking that decisions regarding

intergovernmental finances would be captured by federal-level politicians or

bureaucrats. However, three years after the adoption of the Constitution, no

Commissioners have yet been appointed. In the absence of the appropriate constitutional

leadership, key decisions regarding the vertical and horizontal distribution of

financial resources are being made by the federal government as part of the

regular federal budget process.[1]

The current situation robs the intergovernmental fiscal system of its

independent constitutional guardian, and limits the ability of provincial and

local government officials to meaningfully advocate for their fiscal interests

in the federal system. As such,

operationalizing the NNRFC by appointing a Chairperson and Members—to be done

by the President, on the advice of the Constitutional Council—is a critical

step that needs to be taken as soon as possible.

[1] In countries that have a similar approach to federalism as Nepal (such as Kenya and South Africa), intergovernmental fiscal transfers are purposely not included from the regular national budget formulation process and the annual Budget Act. Instead, in Kenya and South Africa, an annual Division of Revenue Act is adopted prior to the formulation of annual budgets at each level. This approach should be considered in Nepal, as it (a) ensures greater independence between intergovernmental finance decisions and the federal budget, and (b) allows provincial and local governments greater time to prepare their plans and budgets within firm budget ceilings.