Sections 1 – 5 of this primer provide an overview of decentralization and localization; present an introduction to the four basic pillars of intergovernmental finance; and consider the political economy context in which decisions are made with respect to decentralized finance at the national, local and community level. All of this serves as an introductory context for policy makers, policy practioner and development actors in public sector governance, pbulic sector management, as well as in sectors working on services to be delivered at local levels by subnational entities.

Within the range of analytical tools at the disposal of policy makers, policy practitioners, and develpoment advocates, this section aims to: (a) establish a clear link between decentralized public sector finances, effective public sector management and the localization of development; (b) help policy makers and policy analysts place a country’s intergovernmental governance and fiscal arrangements within a spectrum of international experiences that allows them to prioritize areas for potential policy engagement; and (c) based on the reform environment, identify specific interventions that might improve the country’s intergovernmental fiscal “plumbing.”

6.1 Decentralized public sector finances, effective public sector management and the localization development results

An effective, efficient, transparent, and rules-based public financial management (PFM) system is an essential tool for a government in the implementation of fiscal decentralization program. PFM reforms support the fiscal decentralization process by promoting transparency and accountability in the use of public resources, ensuring allocation of public resources in accordance with citizens’ priorities, and supporting aggregate fiscal discipline.

A closer look at the evidence indicates that decentralization does not consequentially translate into better outcomes because of waste, corruption, and inefficiencies. In some countries, the money does not often reach the service delivery units (Reinikka and Svensson 2001); in others, the quality of services is very poor (Chaudhury and Hammer 2003). Furthermore, studies on the impact of decentralization on macro-fiscal indicators cannot unequivocally argue for better economic outcomes (Davoodi and Zou 1998; deMello 2000; Fukasaku and deMello 1998; Martinez-Vazquez and McNab 2006; Jali, Harun, and Mat 2012; Palienko, Oleksii, and Denysenko 2017; Albehadili and Hai 2018).

There are several reasons cited in the literature for the mixed results of decentralization programs. Some of these reasons are related to the intergovernmental fiscal framework, such as misaligned responsibilities, badly designed transfer system, and soft-budget constraint. Others are related to PFM arrangements—for example, political capture, weak accountability links, waste, and the lack of safeguarding measures against abuse, misuse, fraud, and irregularities. In designing a decentralization program, sequencing and implementation of both intergovernmental fiscal and PFM reforms are extremely important.

Decentralizing public sector finances has profound implications for intergovernmental institutions, budgetary processes, and financial arrangements underlying central-local relationship in a country. With the implementation of a decentralization program, the legal and political authority to plan projects, make decisions, and manage public functions is transferred from central government and its agencies to subnational governments. But it is important to realize that once the public administrative system of a country is decentralized, ensuring conformity with the rules and regulations, control of expenditure, and monitoring performance become increasingly complex. Therefore, fiscal decentralization reforms should be designed and implemented within the context of of broader public expenditure reforms.

Public expenditure reforms that aim to improve resource allocation and budget formulation and implementation processes have an impact on three levels of public sector outcomes: (a) aggregate fiscal discipline; (b) resource allocation based on strategic priorities; and (c) efficiency and effectiveness of programs and service delivery (PEFA 2005). They cover a wide range of issues from budget preparation to institutions of public expenditure management and public accountability which are fundamental to policy decisions and economic management. A key challenge for countries in decentralizing public sector finances is to develop coordinated budgetary and financial management reform policies across levels of government to ensure correspondence with national macroeconomic objectives for inflation, growth, and fiscal and monetary stabilization (Ter-Minassian 1997). These objectives have guided considerable efforts to improve PFM practices for central governments around the world. But relatively little effort has been exerted to consider the extent to which the design of the intergovernmental fiscal system, as a whole, supports the achievement of each of the three policy objectives of an effective PFM system, or risks the central government achievements of these goals.

Decentralizing public finances aims to move away from a centralized system, with ex ante controls, to a more decentralized system, with emphasis on ex post monitoring. Without having an effective PFM system at both central and local levels, unintended consequences of a fiscal decentralization program can be fiscal imbalance, weak accountability, political capture, and deterioration in public services.

In many countries, subnational governments lack a coherent PFM structure. Even if they do have one, it might be at odds with the national design. Therefore, as a public administration system becomes more decentralized, there is a need for better coordination of PFM functions across levels of government. This coordination should aim to achieve the following objectives:

- First, PFM systems (at all government levels) should ensure that public sector resources are distributed efficiently across the vertical dimension of the public sector. Here, the bulk of public sector resources reach the service delivery facilities responsible for frontline public service provision, rather than getting stuck at the central ministry level or at an intermediate administrative level. It is impossible to talk about allocative efficiency in a situation where financial resources get stuck at higher government or higher administrative levels.

- Second, PFM systems (at all government levels) should ensure that public sector resources are distributed efficiently and equitably across the national territory. This ensures that places with greater public expenditure needs receive proportionately greater resources. A public sector that does not optimally distribute its financial resources across the national territory in proportion to subnational expenditure needs, whether through centralized or decentralized mechanisms, is at risk of underfunding public sector services in certain locations and thereby failing to be allocatively efficient.[34]

- Third, the intergovernmental fiscal and financial framework should ensure that once funds arrive at the regional or local level (through any mechanism), these resources are efficiently transformed from resources into service delivery and development results. The exact requirements for improving public sector efficiency in different countries and in different locations within a country depends heavily on the specific country context, and care should be taken not to assume that centralized spending is by definition more efficient than devolved spending.[35] It is universally true that a public sector which does not optimally transform its public sector resources into development results in different places across its national territory—in a way that is responsive to different conditions in different locations—fails to achieve operational efficiency.

In order to ensure that fiscal decentralization is structured in a way which enables sustainable development outcomes, it is possible to analyze each of the four pillars of fiscal decentralization in the context of these three elements: vertical fiscal balance across different government levels; horizontal fiscal balance among subnational jurisdictions at different levels; and the efficient use of resources at the subnational level to attain sustainable development outcomes as highlighted below in Table 6.1.

| Assignment of functions/ expenditure responsibilities | Revenue assignment/ own source revenues (OSR) | Intergovernmental fiscal transfers (IGFT) | Borrowing and capital finance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical fiscal balance (between center and subnational levels) | Devolved functions raise subnational expenditure needs; centralized functions require more central funding | Revenues are typically more centralized than expenditures (based on the subsidiarity principle) | Primary role of IGFT is to improve vertical fiscal balance, but can be used to encourage priority spending on certain functions | SNG borrowing provides access to finance, but not to funding (does not alter LT vertical fiscal balance) |

| Horizontal fiscal balance (among subnational jurisdictions) | The horizontal incidence of expenditure needs differs considerably across functions (and between recurrent / capital) | Revenue decentralization often benefits areas (incl. urban areas) with strong economies / natural resources | Unconditional or conditional grants can be equalizing; the mix and incidence of IGFTs is often politically driven | Poorer regions and localities are less creditworthy and have limited funding access |

| Efficient use of resources to attain development outcomes | The production function of public services differs across sectors and localities, and so do appropriate levels of devolution | Under right conditions, devolved finance offers accountability and links revenues and expenditures | The IGFT system may provide disincentives for OSR collection and expenditure efficiency | Private capital finance may impose a degree of market discipline |

6.2 Placing country practices within a spectrum of intergovernmental institutional and fiscal arrangements

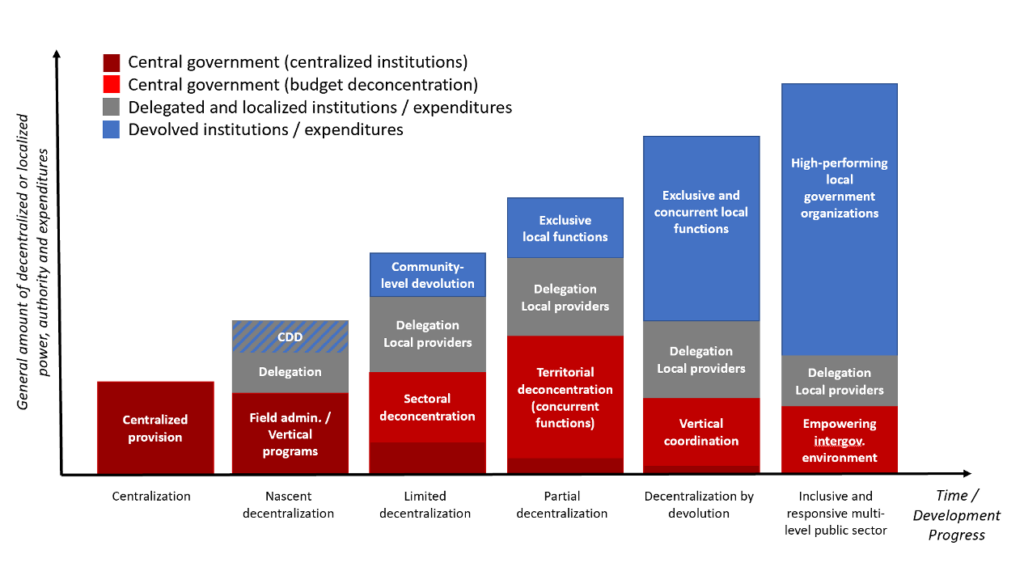

Although decentralization and localization are not linear processes, and even though each country’s decentralization trajectory is unique, it is useful to consider that the general nature and composition of intergovernmental institutional and fiscal arrangements tends to evolve over time and with a country’s state of development from more centralized to more decentralized.[36] No two countries are exactly alike when it comes to the nature of their state of decentralization or intergovernmental arrangements. In addition, there is nothing automatic about the evolution of intergovernmental arrangements as economic and social development takes place in a country. Nonetheless, it might be useful to specify six different generic types of decentralization and localization that reflect a typical” state of institutional and fiscal arrangements or expenditure approaches along the intergovernmental spectrum (Figure 6.1).

The generic typology in Figure 6.1 presents six “textbook” types of intergovernmental arrangements. These range from evolving from a highly centralized institutional and fiscal system, where the central government is paramount and the public sector’s budgetary resources are contained in the budget of the central government without any further decentralization or localization, to gradually more decentralized or localized institutional and fiscal approaches, which typically form intermediate steps on a long-term trajectory from more centralized to more decentralized public sector institutions and expenditures. As suggested by the typology, it is often the case that within a country, and even within the same sector, there is a messy and simultaneous mix of central implementation, delegation, deconcentration, and decentralization happening all at once.

At the lowest state of development, when the central public sector has an extremely limited capacity, as in an immediate post-conflict scenario, the public sector tends to organize itself in a highly centralized manner in order to use its scarce human and financial resources as efficiently as possible. However, highly centralized and concentrated public sectors tend to have major challenges in effectively localizing public services and achieving community engagement. Under such conditions, a first step in improved public services and the legitimacy of state institutions can be achieved through the development of an effective field administration, along with the introduction of vertical sector programs and community-driven development interventions (CDD), and/or delegation of service delivery functions to dedicated service delivery authorities.

In turn, each next step in the typology resolves a common (binding) constraint in the preceding intergovernmental arrangement as countries tend to progress toward a more decentralized and localized public sector as social and economic conditions evolve with the overall level of development. For instance, there tends to be a somewhat natural progression in the nature and organization of the central public sector over time, where at each stage of decentralization, the public sector tries to resolve the main binding constraint of the previous one. This sees the sector move from a fully centralized institutional and fiscal structure to administrative deconcentration, to vertical (sectoral) budgetary deconcentration, and eventually, horizontal (territorial) deconcentration. In turn, a well-functioning system of horizontal deconcentration is also often considered a precondition for effective devolution (Bahl and Martinez-Vazquez 2013).

Similarly, the nature and level of spending by devolved local governments tends to be associated with where countries are on the development spectrum. In low-capacity development contexts, devolution efforts are likely to focus on community-level local jurisdictions – for example, communes or villages – and often involve a limited set of functional responsibilities. As the institutional potential of local governments tends to grow along with the state of development, local governments in more advanced development contexts are able to incrementally take on a more prominent role in public infrastructure development and service delivery.

While it is possible to “jump” one or more stages of the decentralization process, doing so does typically complicate the decentralization or localization reforms. For instance, in recent years, both Kenya and Nepal started their constitutionally-driven devolution reforms with subnational government entities that were created de novo rather than relying on preexisting territorial-administrative jurisdictions. This meant that they had to “build the car while driving it”—building the institutional capacity of subnational governments from scratch at the same time as functional responsibilities were transferred. The decentralization process in these countries posed significantly greater challenges—and risks to service delivery outcomes—when compared to more sequential reforms. For example, the district-level local government organizations empowered by the “big bang” decentralization reforms in Indonesia in 2001 built on previously established (territorially deconcentrated) district administration units. This meant that despite a considerable change in the local political system, the basic management of local administration and local service delivery continued largely uninterrupted.

6.3 Improving the intergovernmental fiscal plumbing: general guidance

Once a public institutional and expenditure review has been conducted in order to identify the exact status and nature of decentralization and localization of a country’s public sector, and once the status can be placed on the spectrum of international experiences as per Figure 6.1, national governments need to consider two possible directions for decentralization reforms.

First, it might be possible to shift towards a more decentralized intergovernmental disposition if there is political momentum for wholesale reform of the entire system of intergovernmental relations. An example is the post-conflict revision of constitutional arrangements. This was the case in the major decentralization reforms in Indonesia, Kenya, the Philippines, and South Africa. In such cases, it is possible to come up with general guidance with regard to possible areas where development partners might contribute in terms of strengthening intergovernmental (fiscal) arrangements (Table 6.2).

Alternatively, in the absence of such momentum or whether the country is merely trying to improve the functioning of the public sector at the margin. Making the existing system work better—by taking where a country is on the decentralization spectrum and improving intergovernmental the system—may involve tweaking or clarifying functional assignments or expenditure management arrangements; improving the collection of local own source revenues; reducing the fragmentation of the transfer system, or improving the ability of local governments to access capital financing as appropriate, in line with the discussions in Section 2-5 above.

However, where policy forces align to not just “improve in place” but take a step toward more effective public sector management and greater decentralization, Table 6.2 can provide useful—although generic—guidance on what steps might be taken at different stages of decentralization and development progress.

In interpreting the guidance in Table 6.2, it should be noted that forward progress may entail not only improvements in devolved intergovernmental finance and strengthening local government financial management. Additionally, it should involve improving the role of the central public sector in a multilevel governance framework, including through better deconcentration and delegation, and by being a better intergovernmental coordinator. Naturally, the general guidance contained in Table 6.2 should be adjusted and operationalized based on a careful assessment of the country’s situation and based on the specific policy objectives for pursuing decentralization or localization. In particular, decentralization and localization reforms may be pursued in order to achieve one or all of the following:

- Improve the overall (allocative and technical) efficiency of the public sector; this is especially relevant in cases where the central public sector is considered to be under-performing.

- Ensure a more inclusive, responsive and democratic public sector.

- Ensure a stable and legitimate public sector, where political economy forces are balanced in a way that prevents (violent) conflict.

- Promote the improved and results-based delivery of public services and achieve development in a socially, economically, and environmentally resilient, inclusive, sustainable, and efficient manner.

In pursuing fiscal decentralization and localization reforms, it is important to remember that the four pillars of intergovernmental finance are not only interrelated with each other, but that in turn, key aspects of fiscal decentralization are inter-related with the political and administrative aspects of decentralization. Something that appears as a technical challenge in the fiscal space—for example, local budget plans consistently favoring community-implemented infrastructure or livelihoods schemes over sectoral investments—may be caused by problems in the intergovernmental political or administrative (planning) context. Likewise, it is critical to review any decentralization or localization reform proposal through a political economy lens. Who are the winners and losers in the proposed reforms, and will key stakeholders, through the narrower lens of their own political or institutional interests, agree to the proposed reforms?

[34] One example of this is the economic loss associated with underfunding public education in rural areas, which can result in “lost Einsteins” and slower economic growth (Bell et al 2018).

[35] For instance, in many developing and transition countries, public sector payrolls (for teachers and healthcare workers) are largely controlled or managed in a central fashion. In these cases, to the extent that public sector salaries represent the largest category of central government spending, to what degree do absenteeism and other human resource challenges result in inefficient service delivery in different locations?

[36] For further background and details, see: Decentralization, Multilevel Governance, and Intergovernmental Relations: A Primer (LPSA/World Bank 2022).