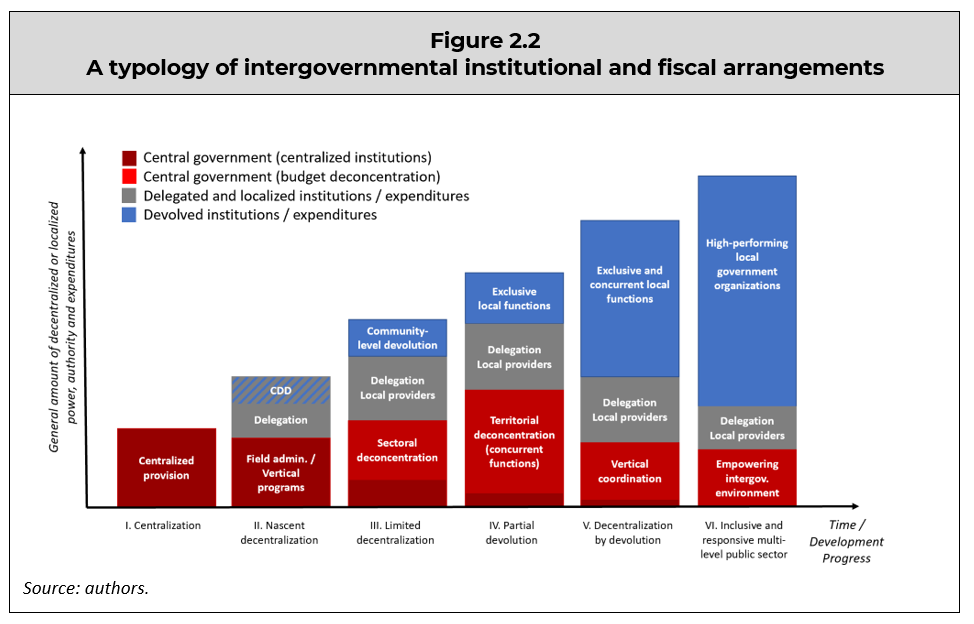

No two countries are exactly alike when it comes to the nature of their state of intergovernmental arrangements. Additionally, there is nothing automatic about the evolution of intergovernmental arrangements as economic and social development takes place in a country. Nonetheless, it might be useful to specify six different generic types of decentralization and localization that reflect a “typical” state of institutional and fiscal arrangements or expenditure approaches along the intergovernmental spectrum (Figure 2.2).

The generic typology in Figure 2.2 presents six “textbook” types of intergovernmental arrangements. From a highly centralized institutional and fiscal system, where the central government is paramount and the public sector’s budgetary resources are fully contained in the budget of the central government without any further decentralization or localization, arrangements can evolve to more decentralized or localized institutional and fiscal approaches. These approaches typically form intermediate steps on a long-term trajectory from more centralized to more decentralized public sector institutions and expenditures. As suggested by the typology, it is often the case that within a country, there is a simultaneous (and often messy) mix of central implementation, delegation, deconcentration, and decentralization happening all at once across and even within sectors, and types, and levels of subnational government.

At the lowest state of development, when the central public sector has an extremely limited capacity – for instance, in an immediate post-conflict scenario – the public sector tends to organize itself in a highly centralized manner in order to use its scarce human and financial resources as efficiently as possible. This was the case in post-conflict Sierra Leone, prior to the adoption of Local Government Act of 2004. Very few countries, if any, permanently remain in this state of complete centralization.

Despite some theoretical advantages to centralized governance and administration, highly centralized and concentrated public sectors tend to have major challenges in effectively localizing public services and achieving community engagement. Under such conditions, a first step in improving public services and increasing the legitimacy of state institutions can be achieved through the development of an effective field administration, along with the introduction of vertical sector programs and community-driven development (CDD) interventions. These may be coupled with delegation of service delivery functions to dedicated service delivery authorities. For instance, in Afghanistan, the National Solidary Program introduced Community Development Councils (CDCs) in 2003 in order to bring the public sector closer to the people (World Bank 2015).

In turn, each next step in the typology resolves a common (binding) constraint in the preceding intergovernmental arrangement as countries tend to move towards a more decentralized and localized public sector as social and economic conditions evolve with the overall level of development.[10] For example, there tends to be a somewhat natural progression in the nature and organization of the central public sector over time, where at each stage of decentralization, the public sector tries to resolve the main binding constraint of the previous one. So, from a fully centralized institutional and fiscal structure to administrative deconcentration, to vertical (sectoral) budgetary deconcentration, and eventually, horizontal (territorial) deconcentration.[11] In turn, a well-functioning system of horizontal deconcentration is also often considered a precondition for effective devolution (Bahl and Martinez-Vazquez 2006).

Similarly, the nature and level of spending of devolved local governments tends to be associated with where countries are on the development spectrum; in low-capacity development contexts, devolution efforts tend to focus on community-level local jurisdictions, such as communes or villages, and often involve a limited set of functional responsibilities. As the institutional potential of local governments tends to grow along with the state of development, local governments in more advanced development contexts are able to incrementally take on a more prominent role in public infrastructure development and service delivery.

While it is possible to “jump” one or more stages of the decentralization process, doing so does typically complicate the decentralization or localization reforms. For instance, in recent years, both Kenya and Nepal started their constitutionally-driven devolution reforms with subnational government entities that were created de novo rather than relying on preexisting territorial-administrative jurisdictions. This meant that they had to “build the car while driving it” – that is, build the institutional capacity of subnational governments from scratch at the same time as functional responsibilities were transferred. The decentralization process in these countries posed significantly greater challenges and risks to service delivery outcomes when compared to more sequential reforms. For example, the district-level local government organizations empowered by the “big bang” decentralization reforms in Indonesia in 2001 built on previously established (territorially deconcentrated) district administration units. This meant that despite a considerable change in the local political system, the basic management of local administration and local service delivery continued largely uninterrupted.

| Box 2.1 Different types of deconcentration In countries that do not have elected local government levels, the local public sector is typically formed by “deconcentrated” subnational line departments or subnational territorial units of the national government, which form a hierarchical, administrative tier of the higher-level government. In these countries, these deconcentrated subnational administrative units are generally assigned the responsibility for delivering key government services such as education, health services within their respective geographic jurisdictions. As such, in a deconcentrated system, the provincial education department or the district education office (for instance) might be a suborganization of the national Ministry of Education, rather than reporting to any elected local council. Even in countries that do have elected local governments, some or most public services may be delivered through deconcentrated administration units. Because deconcentrated departments or jurisdictions are merely a hierarchical part of the next-higher government level, unlike local governments, deconcentrated units are not corporate bodies. Nor do deconcentrated jurisdictions have their own budgets; instead, their budgets are typically designated as suborganizations within the budget of the higher government level. In deconcentrated systems, “local” government officials are an integral part of the national public service, and local executives, such as regional or district governors, as well as local department heads, are generally appointed by the central government. In some countries, central line ministries are organized administratively or organizationally in a deconcentrated manner, while the deconcentrated entities are not recognized as separate budget entities in the country’s budget structure. This is generally known as administrative deconcentration. In contrast, budgetary deconcentration can be defined as a situation in which deconcentrated entities (i) form an organizational part of the national (state) administration; (ii) deliver public services or perform its functions in accordance with a territorial mandate; and (iii) constitute a formal budgetary entity in the Chart of Accounts (along the organizational dimension of the budget). In addition, it may be helpful to further divide deconcentrated public sector structures – or deconcentration of budget structures – into two different types of deconcentration: vertical or sectoral deconcentration versus horizontal or territorial deconcentration. The hallmark of a vertical (or sectoral) deconcentrated structure is that line ministry budgets are organizationally distributed across different government levels or tiers, so that subnational (provincial or district) line departments service as separate suborganizations and cost centers within their line ministry budgets. From an institutional and budgetary viewpoint, this means that every line ministry follows a “silo-structure” or a “stove pipe” from the central level down to the province level, and possibly to district level. Vertical deconcentration allows line ministries a strong role in planning and implementing sectoral services. Under a horizontal (or territorial) deconcentrated budget structure, subnational line departments are not included in the budget under their parent ministries. Instead, subnational revenues and expenditures are included in the central budget and aggregated into territorial units, which are then broken down into subnational departments. As a result, under horizontal (or territorial) deconcentration, sectoral departments at each administrative level are administratively subordinate (for example) to the Provincial Governor or to the District Governor, respectively. As such, under horizontal deconcentration, the subnational budget reflects the aggregation of spending decisions made by the center to be executed within the subnational jurisdiction. However, since the subnational spending is no longer contained with the budget votes of individual line ministries, subnational officials are better able to coordinate their efforts across sectors and may have greater discretion over subnational expenditures in order to respond better to local priorities. Source: LPSI Handbook (2012). |

[10] Although it is difficult to precisely match real-world public sector systems to these textbook decentralization types, Bangladesh and Cambodia might serve as examples of limited decentralization (Type III); Mozambique might offer an example of partial devolution (Type IV); Indonesia, Kenya, Nepal are examples of full devolution (Type V), while Denmark might offer an example of an inclusive and responsive multilevel public sector (Type VI).

[11] Administrative deconcentration without corresponding budget deconcentration (i.e., relying on deconcentrated field offices without giving them some degree of resource autonomy) tends to result in vertical imbalances between human resources and finances within the government administration. This constraint can most easily be resolved by introducing budgetary deconcentration within each sector ministry budget. However, because under a vertical or sectoral approach to deconcentration, each line ministry operates ‘vertically’ in a deconcentrated manner, this approach typically does not allow for much—if any—harmonization of planning and budgeting across sectors at the provincial or district level. In turn, this challenge can be resolved at the appropriate time by shifting from vertical (sectoral) deconcentration to horizontal or territorial deconcentration.