As suggested by the discussion above, the analysis of decentralization, multilevel governance, and intergovernmental relations requires considering the effectiveness and inter-relationship between public sector stakeholders at different government levels. Furthermore, effective decentralized and/or intergovernmental governance arrangements represent a critical component in the efficient delivery of frontline services and in achieving sustainable development results. As such, it is critical to place the different dimensions and elements of decentralization and intergovernmental relations in the larger multilevel governance framework (Figure 1.2).

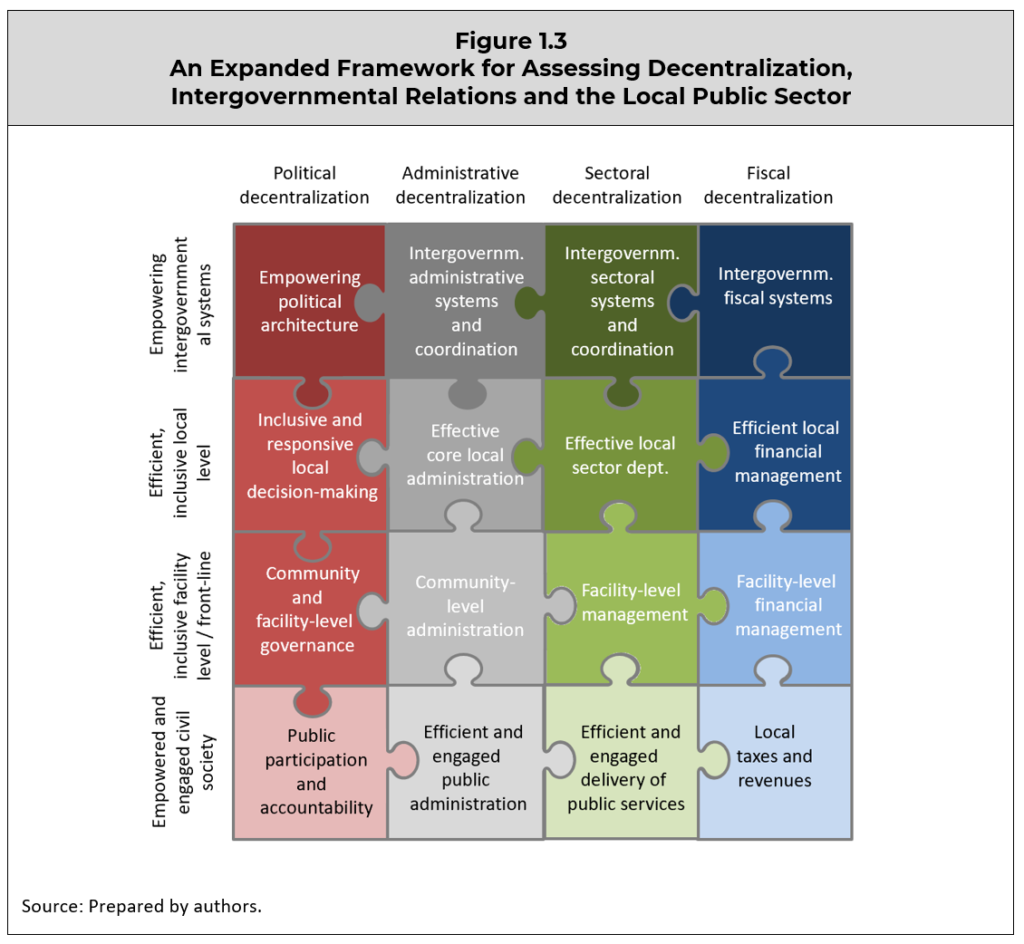

The assessment framework for decentralization, intergovernmental relations, and the local public sector presented above in Figure 1.2 combines two critical aspects of an effective system of intergovernmental relations. First, decentralization has political, administrative, and fiscal dimensions, which must be coordinated and balanced in order for decentralization to be successful and effective (Panel A). Second, effective multigovernance systems require action and coordination across three levels, requiring empowering intergovernmental architecture and systems; efficient, inclusive and responsive local governments and/or other local institutions; and an engaged civil society, citizenry, and local private sector (Panel B). The resulting assessment framework for decentralization, intergovernmental relations, and the local public sector is formed by a 3 X 3 matrix with 9 different cells, where each of these cells represents an integral part of an effective multilevel public sector.

Institutionally, each cell in this matrix corresponds to one or more different institutional stakeholders or actors at each level in the public sector. For instance, central government is not a consolidated, institutional entity or actor, but rather, a constellation of different political, administrative, and fiscal bodies (central ministries, departments and agencies), which sometimes collaborate towards a common purpose, while at other times (tacitly or actively) oppose each other.[8] Likewise, local governments are also not unified institutional entities: local governments comprise of a number of different local political bodies or actors (the mayor, the council); local administrative actors or departments (chief administrative officer, chief planning officer, chief human resource officer, local sectoral departments); and local financial actors (Finance Department, Revenue Administration Unit, Internal Control Unit).

In turn, each of the stakeholders at each level need three attributes in order to be effective across the spectrum of political, administrative, and fiscal decentralization and empowerment (World Bank 2008, 2009; Boex and Yilmaz 2010). First, each stakeholder needs the discretion and authority (the legal power and administrative discretion) to perform their functions or responsibilities. Second, stakeholders at each level need to have the necessary organizational structure and systems in place and the institutional capacity to perform their functions. Third, accountability mechanisms need to be in place for stakeholders at each level to be held accountable for their performance. Furthermore, functioning arrangements for inter- and intra-governmental coordination and cooperation are required across and between levels.

The analytical framework visualized in Figure 1.2 provides a general framework which may be fine-tuned to be suitable to a specific country or sector context depending on the exact purpose or focus of intergovernmental fiscal analysis. For instance, it may be useful to reflect the role of regional or intermediate level governments in the analytical framework.

In other cases, it may be useful to divide the local government (or local administration) level into two distinct sublevels – the local government (administration) headquarters level as distinct from the frontline service delivery unit or local facility level. This distinction is particularly relevant in places where frontline facilities have distinct de jure or de facto planning, budgeting, or administrative and managerial power.

Similarly, when the impact of decentralization or intergovernmental (fiscal) systems is discussed for one or more specific sectors, it might be useful to separate out decentralization concerns that apply to a single sector from more general elements of administrative decentralization (such as the role of the Planning Commission or the Civil Service Department) by adding a “sectoral decentralization and empowerment” column in the diagram (see Figure 1.3).

This allows for more detailed analysis of sector-specific elements, as optimal sectoral arrangements may vary from sector to sector. This sectoral column can then allow a greater focus on sector-specific subsystems, such as the formulation and implementation of sectoral policies, plans and regulations; sectoral HRM issues; and sector-specific supply chains; as compared to administrative constraints outside the purview of the sector ministry.

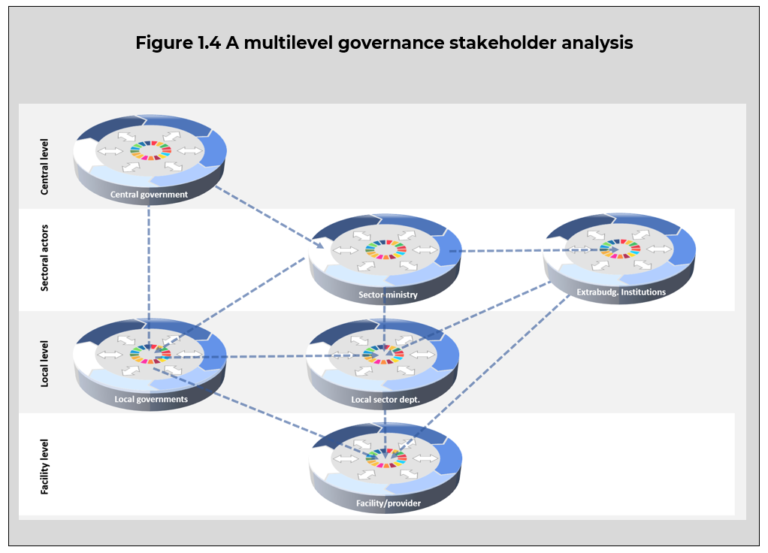

The framework presented in Figure 1.3 is largely conceptual in nature. A first step applying this conceptual framework to a specific country and/or sector context would involve the preparation of a comprehensive overview of the different stakeholders directly or indirectly involved in delivering frontline public services. Such a public sector institutional analysis should be done in such a way that allows policy makers and policy analysts to not only consider the strengths and weaknesses of all stakeholders or public sector entities involved, but also in a way that allows the team to identify where the distribution of functions, powers, and resources – in addition to coordination among different stakeholders – may form a binding constraint to effective and responsive service delivery (Figure 1.4).[9]

[8] For instance, Parliament, the Office of President or Prime Minister, and national political parties are key central-level political actors. The Ministry of Planning (or Planning Commission) and the Civil Service Department are key central-level administrative stakeholders or actors. The Ministry of Finance, the National Treasury (and/or the Accountant-General’s Officer), and the National Audit Office are key central-level finance stakeholders.

[9] Please refer to the World Bank’s GovEnable documentation on decentralization and multilevel governance for more detailed guidance on how to operationalize related public institutional governance and expenditure reviews.