Kenya adopted a new constitution in 2010 based on a two-tiered devolved government system, which assigned many formerly central government public service delivery responsibilities to a new level of county governments. As an institutional response to longstanding grievances, this radical restructuring of the Kenyan state had three continuing main objectives: decentralizing political power, public sector functions, and public finances; ensuring a more equitable distribution of resources among regions; and promoting more accountable, participatory, and responsive government at all levels. Three rounds of national and county elections (held in 2013, 2017, and 2022) resulted in successful transitions of political and administrative power that place important service delivery responsibilities at the county level. Although Kenyans associate devolution with certain dividends brought about by the constitution, different aspects of Kenya’s multilevel governance structure—including increasing public participation and accountability, improving county administration and services, and ensuring an equitable and efficient use of public finances at all levels—continue to be a work in progress.

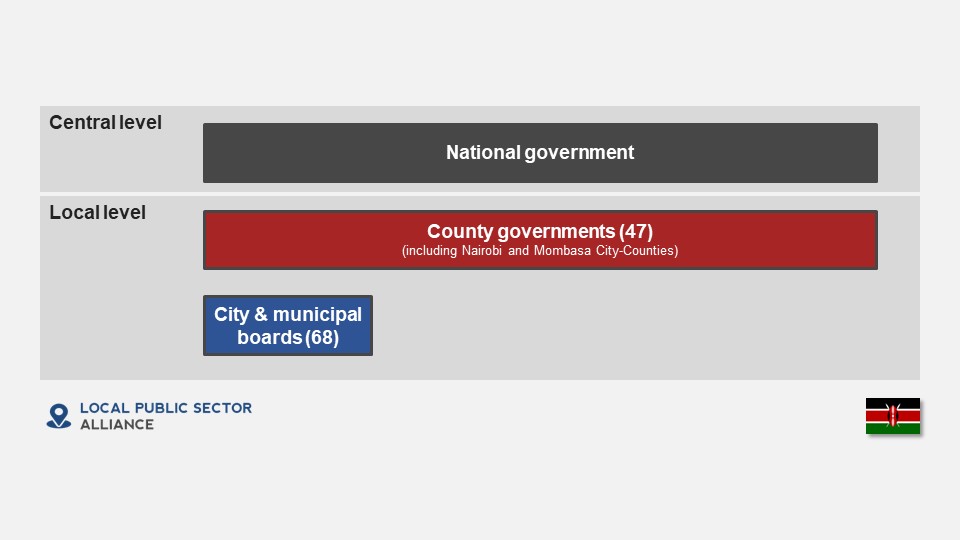

Subnational government structure

The first elections under the new constitution were held in 2013 and led to the establishment of 47 new county governments. Each county government is made up of a County Executive, headed by an elected governor, which works under the oversight of an elected County Assembly. County governments fulfill their constitutionally mandated responsibilities, financed by annually prescribed shares (“equitable shares”) of national revenues; their own sources of revenues (own-source revenues); and various conditional grants from the national government and development partners. The 2010 constitution abolished the elected local governments that previously existed; instead, the post-devolution legal framework established cities and municipalities with appointed urban boards. Although County Governors were initially hesitant to establish municipal boards, the World-Bank supported Kenya Urban Support Project (KUSP, 2017-2023) provided counties with support and incentives to establish urban boards. In addition to the City-Counties of Nairobi and Mombasa and two cities (Nakuru and Kisumu), by 2023, county governments had established 66 municipal boards.

Nature of subnational governance institutions

Each county government is a constitutional, legal, and de facto body corporate made up of a county executive, headed by an elected governor, and an elected County Assembly that legislates and provides oversight. Each county has its own County Public Service Board to establish and abolish offices in the county public service; appoint persons to hold or act in offices of the county public service (including in the boards of cities and urban areas within the county); and to perform other human resource management functions. The County Secretary, recruited by the county government’s political leadership under the County Governments Act (2012), is the head of the county public service. In contrast to the political, administrative, and budgetary autonomy and authority enjoyed by County Governments, the governance and management of urban areas and cities is based on a principal-agency relationship between the boards and their respective county governments. Although cities and municipalities are de jure corporate bodies under the Urban Areas and Cities Act (2011), in practice, they are non-devolved institution (i.e., not de facto corporate entities with autonomy and their own authority), as their board is appointed by the county government; the municipal manager is appointed and employed by the county government; and their budgets are generally included in the county budget as a county budget vote. Municipal boards further generally lack the authority to manage their own funds.

Functional assignments

The Constitution laid out a strong foundation for sharing responsibilities and resources between the National and County governments, with Counties being assigned significant powers and frontline service delivery functions, including agriculture and livestock services, county health services, county transport, planning and development; county public works, including water and sanitation, pre-primary education and childcare facilities, and other services. Although the Transition Authority had envisioned a more gradual transfer of functional responsiblities, County Governors demanded–and received–the transfer of facilities, functionaries and funds associated with their constitutional mandates in 2013. The national government retains the power of primary and secondary education, while assuming a typically “central” mandate around policy, standards, and norms. A constitutional guarantee of unconditional transfers from the national government, county governments were expected to have the means and the autonomy to begin to address local needs. Although County Governments are the de facto frontline service providers in a wide range of functions, their ability to perform these functions continues to be limited by a relatively high degree of centralization of fiscal resources, and a lack of intergovernmental coordination and cooperation in different sectors.

LoGICA Assessment

LoGICA Intergovernmental Profile: Kenya 2023 (Excel)

Selected resources

Kenya Country Profile (World Observatory on Subnational Governance and Investment, OECD/UCLG)

The Local Government System in Kenya (Commonwealth Local Government Forum)

Local government country profile: Kenya (UN Women)

Making Devolution Work for Service Delivery in Kenya (Muwonge et al, 2022).

Back to Local Public Sector Alliance Intergovernmental Profiles – Country Page

Last updated: September 22, 2023