A long-running debate in decentralization circles asks whether local governments function better under elected leaders or appointed bureaucrats. Advocates of political decentralization emphasize accountability, community voice, and responsiveness, while supporters of technocratic administration highlight expertise, impartiality, and resistance to local capture.

A recent study from Karnataka, India—posted on the Ideas for India website—offers unusually rigorous evidence that helps move this debate beyond ideology. By taking advantage of a natural experiment created when COVID-19 disrupted local elections, the study reveals when elected leaders outperform bureaucrats and when bureaucrats deliver better results. The findings offer valuable lessons for decentralization reforms globally.

A Natural Experiment in Local Governance

Under India’s constitutional framework, rural local governments (Gram Panchayats, or GPs) are normally governed by elected councils with five-year terms. When the pandemic forced the postponement of elections in 2020, the state government appointed GP Administrators—local bureaucrats—to run day-to-day affairs in thousands of villages. As a result, otherwise similar local governments were governed under two different institutional arrangements: some by elected leaders, others by appointed administrators. Because the assignment was driven by the accidental timing of election delays, the authors were able to compare the performance of more than 6,000 GPs in a quasi-experimental way.

The research team combined administrative records, public expenditure data, beneficiary lists, satellite indicators, and citizen surveys. Their goal was not only to measure service delivery, but also to understand how different types of leaders respond to crises, prioritize community needs, and manage inequities across social groups. The study’s broad empirical base provides a rare, data-rich look at how political and administrative leadership models perform in otherwise similar settings.

Responsiveness, Equity, and Expertise

One of the clearest findings is that elected leaders are more responsive to citizen preferences. In GPs led by elected officials, spending patterns aligned more closely with what residents said they valued, and public meetings and participatory processes were more frequent. During the pandemic, this translated into faster and broader social assistance: more workdays under India’s rural employment guarantee program, higher enrollment of new beneficiaries, and stronger oversight of frontline workers. These effects illustrate the information and motivational advantages that elected leaders often possess. Their accountability to constituents appears to drive more active engagement with community needs, especially during crises.

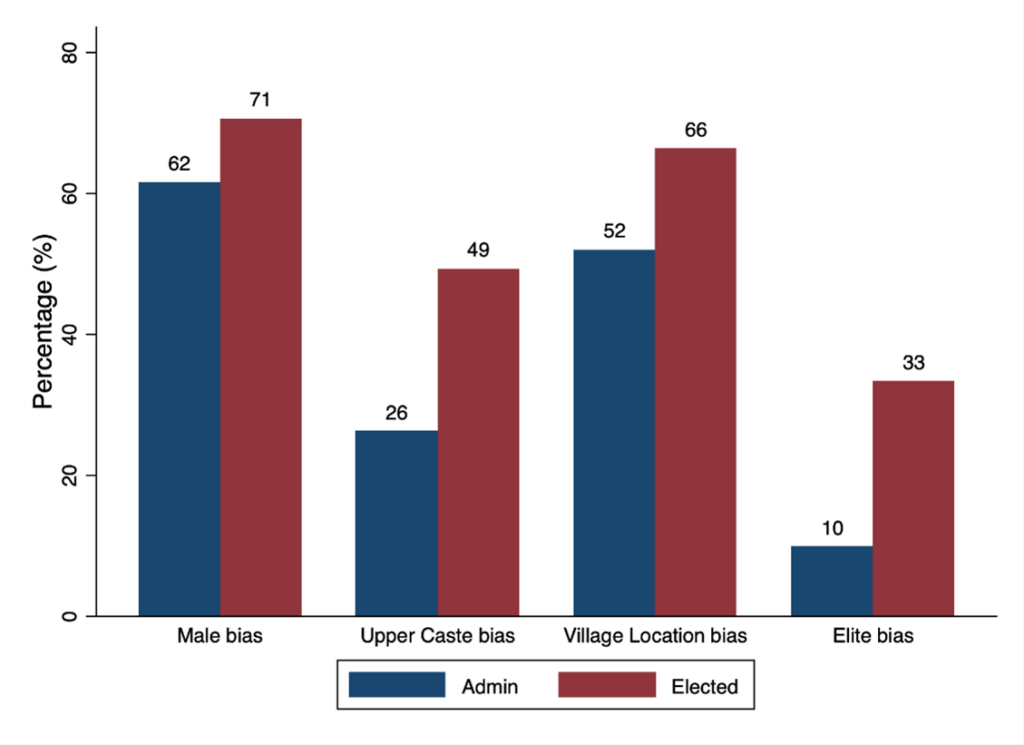

Yet responsiveness came with notable trade-offs. Because elected leaders tended to prioritize the most vocal or influential groups, service delivery improvements were not evenly distributed. Socially advantaged communities—men, upper-caste households, and residents of central village areas—benefited more than marginalized groups. Bureaucrat-led GPs showed lower disparities, suggesting that administrative decision-making, while less responsive overall, tended to be more even-handed across social categories. This distinction highlights a fundamental challenge in political decentralization: responsiveness can inadvertently amplify pre-existing inequalities unless safeguards and inclusion mechanisms are intentionally built in.

The study also shows that bureaucrats outperformed elected leaders in tasks requiring technical expertise. When GP Administrators had professional experience related to specific projects—such as water supply, engineering, rural development, or fisheries—project implementation improved significantly. These results confirm a core principle familiar to decentralization practitioners: technical problems often require technical solutions. Administrative leaders, insulated from short-term political incentives, may be better suited to handle specialized functions that demand continuity, expertise, and compliance with engineering or sectoral standards.

Interestingly, the study found little difference between the two leadership models on indicators with long-run horizons or substantial externalities, such as agricultural productivity (measured through vegetation indices), nighttime lights (a proxy for economic activity), or most pandemic health outcomes. These outcomes appear less sensitive to short episodes of different leadership structures, reminding us that local governance reforms often take time to influence broader development trends.

Lessons for Decentralization: Matching Actors to Tasks

The central takeaway from the Karnataka study is that neither elected leaders nor bureaucrats are categorically superior. Instead, each type of actor performs better under different conditions. Elected leaders excel when local information, citizen engagement, and frontline oversight are essential. Bureaucrats excel when implementation depends on technical proficiency or specialized knowledge. If decentralization reformers treat one model as universally preferable, they risk misaligning responsibilities and weakening local performance.

For practitioners designing or revising decentralization frameworks—whether in federal systems, post-conflict municipalities, African counties, or large metropolitan regions—the Karnataka case suggests the value of “actor–task matching.” Rather than assigning all powers to elected councils or all implementation to bureaucratic arms, institutional design should differentiate the roles. Elected officials may be best placed to set local priorities, engage communities, and ensure accountability. Administrative leaders may be better suited to execute technical projects, manage complex systems, and sustain program quality across electoral cycles.

At the same time, the study highlights the need to address inequality risks in politically decentralized systems. Responsive governance must be paired with mechanisms that ensure inclusion—transparent targeting, community scorecards, gender-sensitive participation processes, and simple digital disclosures that reduce the scope for elite influence. Without these safeguards, political responsiveness can unintentionally reinforce existing patterns of privilege.

Conclusion: Beyond the Politician–Bureaucrat Dichotomy

The Karnataka experience offers a powerful reminder that decentralization is not a choice between politicians and bureaucrats. Effective local governance depends on designing institutions that harness the comparative strengths of both. When elected actors and administrative professionals each operate in domains suited to their capabilities, local governments become more responsive, more fair, and more effective. For decentralization reformers worldwide, this study provides empirical grounding for a more nuanced, more pragmatic, and ultimately more successful approach to building strong local governance systems.

The article summarized by this blog is published on Ideas for India and can be accessed here.

Note: The Feature Image for this blog post was generated with the help of AI.