Amid swirling uncertainties created by internal party wrangling and a second wave of Covid-19, all seven of Nepal’s provincial governments, newly created by the 2015 constitution, introduced their budgets for FY 2021/22 on June 15, meeting the statutory deadline. But Nepal’s halting progress towards fiscal federalism, in place only since the elections of 2017, still has some serious kinks to work out.

As expected, and in line with federal priorities, the new provincial budgets make health security and economic recovery from the pandemic their top priorities. Like last year, all the provincial budgets are focused on fighting Covid-19, through infectious-disease control, expanded healthcare services, and the development of health-related infrastructure and human resources. This penultimate round of budgets before next year’s provincial elections also emphasizes rapid economic development, poverty reduction, advancement for backward areas and communities, expansion of social security, and improvements in living standards.

Despite limited capacity and resources, compounded by federal neglect, the provinces have made considerable progress in the step-by-step, year-by-year process of building a functional system of public financial management (PFM). The new federal system merged and sometimes split districts to create the provincial governments, and there was no comprehensive documentation of their demographic, administrative, and economic profiles—what are the public services and utilities; where are the factories and banks; what are the administrative boundaries. The provinces have since worked hard to create these provincial profiles, pass essential legislation, and assemble the building blocks of effective PFM: periodic development plans, medium-term expenditure frameworks, and guidelines and procedures for the regular work of planning and budgeting.

While these are positive steps in the consolidation of the new federal system, a closer look at these budgets and their development reveals some significant shortcomings. A study of provincial PFM published early this year by The Asia Foundation, Planning and Budgeting in the Provinces of Federal Nepal, found that many weaknesses of the previous system of government appear to have persisted under the current budget regime.

Major shortcomings of provincial PFM identified by the study include weak participatory practices in planning and budgeting, failure to publish programs and budgets in a timely manner, allocation of resources for poorly specified small projects, assignment of large proportions of the budget to the “miscellaneous” category, allocation of funds to the discretionary “constituency development” fund, inadequate and poorly managed capital investment, and inadequate public disclosure of government spending.

There are several formal bodies established to promote intergovernmental consultation and coordination, including the Provincial Coordination Council, the Interprovincial Council, the National Coordination Council, and the Intergovernmental Fiscal Council, but these forums have been largely ignored by the federal government and the provinces alike, with the inevitable result that budgets and other major policies sometimes leave gaps and other times overlap between the different levels of the federal system. And while the provinces make plenty of noise about their exclusion from federal policymaking, their own outreach to local governments to participate in provincial budgeting and policymaking has been equally inadequate.

Continuing a practice that gives excessive discretion to the executive branch to make ad hoc expenditures, often under the influence of political interests, five of the seven provinces have allocated an average of 8.4% of their budgets to the “miscellaneous” line item this fiscal year. This does, admittedly, represent some improvement. Last year the average was 10.7%, and in FY 2019/20, the miscellaneous line item averaged around 17.3% of provincial budgets—with a high of 29.5% in Province 2.

Undermining the limits set by the National Planning Commission (NPC), an apex federal body meant to guide development planning, the provinces have again allocated funds to small-budget programs that overlap with functions of local governments. Per the NPC, development projects worth less than roughly USD 85,000 should be delegated to local governments. In FY 2019/20, Province 1 had 675 projects below this threshold, and in FY 2020/21 Bagmati Province alone had 858 programs below USD 85,000, mostly small infrastructure projects. On the one hand, this practice undermines the functional autonomy and responsibility of local governments. On the other, it leads to duplication of effort at the local and provincial level that creates conflict and wastes scarce resources.

Although the federal budget has discontinued the practice this fiscal year, Province 2 has allocated around 7% of its budget for a “constituency development” fund, which gives members of the provincial assembly discretionary funds to invest in projects of their own choice.

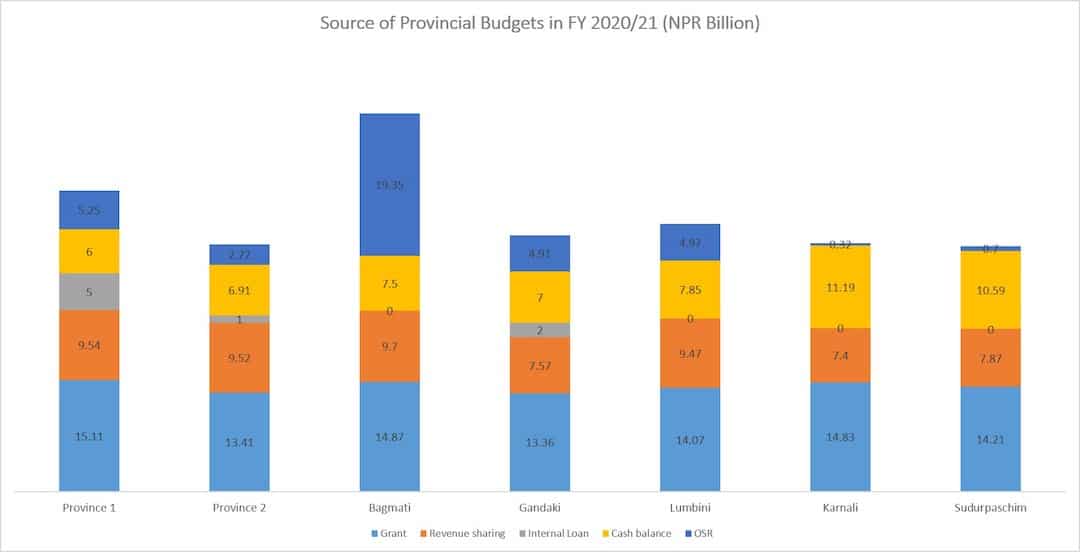

The own-source revenue (OSR) base is bleak for the provinces, and revenue collection is poor. The average proportion of OSR in provincial budgets in FY 2019/20, 2020/21, and 2021/22 was estimated at 11.24%, 14.47%, and 13.58%, respectively. In the current fiscal year, projected OSR ranges from a tiny 1.6 % of the budget in Karnali Province to a more robust but still troubling 41.2% in Bagmati Province. However, it is unclear whether these projections were met in the previous fiscal years, nor is there reliable data for all provinces or consistency in how these values are calculated.

Provincial sources of OSR are limited to vehicle taxes, house and land registration fees, and a tax on entertainment and advertising of which 40–60% is earmarked for local governments. Though provincial OSR has been rising nominally, there have been no major policy changes to reduce dependency on federal fiscal transfers, which are expected to fall due to the pandemic economy.

Despite an early focus on developing institutions, procedures, and management capacity for their new fiscal responsibilities, the provinces have still been unable to spend more than 70% of their annual budgets, on average, and most of this spending is done in a rush in the last fiscal quarter. Given the lack of progress on procurement-system reforms at all levels of government, this situation is unlikely to change in the latest budget cycle.

Inconsistency and incoherence in planning and budgeting are not limited to the provinces, however. All three levels of government have encroached on the jurisdictions of others in key areas such as revenue, healthcare, education, and infrastructure development. Local governments have an exclusive mandate to manage secondary education, yet federal funding of the Education Development and Coordination Unit locks in federal control over the hiring and transfer of teachers and the development of local education materials. Similarly, the federal government, through its budgeting practices, maintains control over the Department of Local Infrastructure, the National Rural Transportation Improvement Program, the Suspension Bridge Division, and small irrigation projects around the country, which by their nature would be better managed at the local level.

Following years of conflict and unrest, Nepal broke with its long history of rule from the center and established a federal system to better serve its diverse population. But without effective fiscal management at the subnational level, federalism cannot ultimately deliver on its promises. As the fate of the country’s federal restructuring hangs in the balance, swift changes are needed, or the functional autonomy of the provinces will remain a distant dream.

This article originally appeared in InAsia, the official blog of The Asia Foundation.

Read the full report by The Asian Foundation: Planning and Budgeting in the Provinces of Federal Nepal.

Bishnu Adhikari is director of governance programs, Parshuram Upadhyaya is a senior governance advisor, Amol Acharya is a senior program officer, and Abhas Ghimire is a consultant for The Asia Foundation in Nepal. They can be reached at bishnu.adhikari@asiafoundation.org, parshuram.upadhyaya@asiafoundation.org, amol.acharya@asiafoundation.org, and abhas.ghimire@asiafoundation.org, respectively. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors, not those of The Asia Foundation.