The Kathmandu Post reports that lawmakers in Nepal have objected to the Local Body Restructuring Commission (LBRC)’s proposal to carve out 565 local units across the country as part of the local body restructuring, saying that the LBRC’s work is unscientific and out of place.

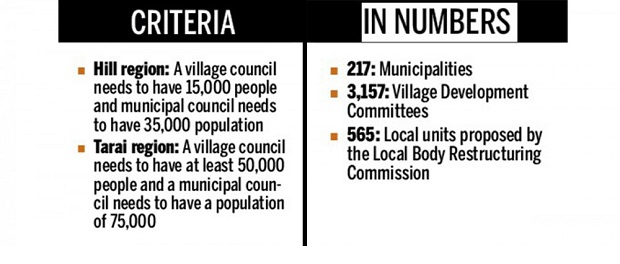

The LBRC was formed in March 20016 to determine number and borders of village councils, municipal councils and special, protected or autonomous regions. In July, the LBRC led by former Secretary Balananda Poudel proposed 565 local units, making administrative divisions based on population size. The propoaed criteria suggest that a village council needs to have 15,000 people in the mountain region while the number has to be at least 50,000 in the Tarai region. Similarly, a municipal council in hills needs a minimum of 35,000 residents while the requirement for the Tarai region is 75,000.

Addressing a meeting of the Legislature-Parliament, the Kathmandu Post reports that lawmakers from different parties said that the number of local units at 565 is too small. Lawmakers argue that this will create problems for the general public when it comes to accessing state facilities and government services. Some lawmakers even demanded that the LBRC be dissolved, as it was “making unscientific recommendations without seeking suggestions from local bodies”.

However, in judging the recommendations of the LBRC, it is important to recognize the true source of concerns for the political parties, as the proposals over the structure of the local government level in Nepal are taking place amidst a political tug-of-war.

In this tussle, politicians and political parties are trying to maximize their power at the provincial level in the new federal system by minimizing the power of local governments. Having lots of small local jurisdictions in each province will allow provincial politicians and ethnically-based political parties to “divide and rule”, thus ensuring that provincial governments will have a political power monopoly in their respective jurisdictions. Furthermore, it is clear that small local governments will not have the administrative capacity to effectively deliver local services. When inefficiently small local governments predictably fail to deliver their constitutially-mandated functions and public services, the provincial-level politicians would be the first in line to take over their functions, facilities, functionaries and funds. Yet, as political leaders at the national and provincial levels gain in power, the people will continue to suffer from weak or absent local services.

The LBRC made a political courageous decision by honoring the intent of the constitution and by proposing a minimum thresholds for local jurisdiction size to ensure that local governments have a “minimum efficient scale” to deliver their constitutionally-mandated services. In doing so, they adhered to the true meaning of decentralization, which is the “empowerment of the people, through the empowerment of local governments”. To the extent that the new constitution intended to reduce the “capture” of the ruling political class over the public sector in order to ensure the needs of the people are met, the proposed local government structure put forth by the LBRC is a strong first step.

For more reporting on the implementation of Nepal’s new federal consitution, see:

http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2016-08-24/implementing-federalisation.html

This post was prepared by Jamie Boex (jamieboex@gmail.com), the director of the Local Public Sector Initiative, based on the reporting by the Kathmandu Post. The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author.